Hey, if you've got a few minutes, there's someone I'd like you to meet.

This is Flight Officer Forrest E. Currier, United States Army Air Force. His friends called him Fod. I don't know why, but I can tell you that where he came from—Aroostook County, Maine—they had kind of a way with nicknames in the mid-twentieth century. My people all come from up there, and whenever they get to talking about the old days, men with inexplicable nicknames like "Boob", "Stump", and "Chick" come up all the time.

Anyway, that's neither here nor there. The fact is that, for whatever reason, he was called Fod, and as Fod we shall know him. He was born in 1911 in Mapleton, Maine, a farming town outside Presque Isle, and lived most of his life in nearby Ashland. Farming was a tough way to make a living, then as now, and the County was and is a hard place to do it, so Fod's early life could justifiably be summarized with that hackneyed old biographical word hardscrabble.

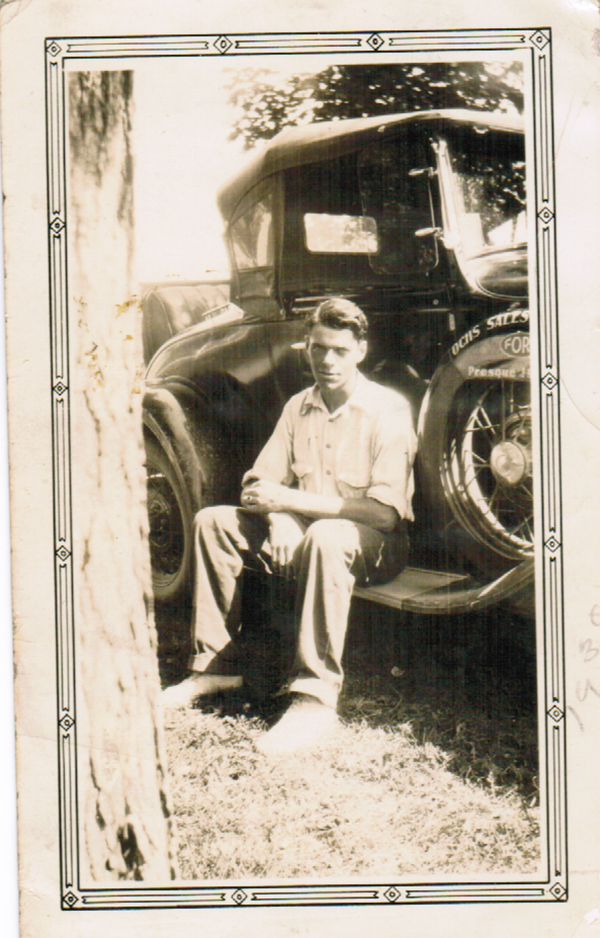

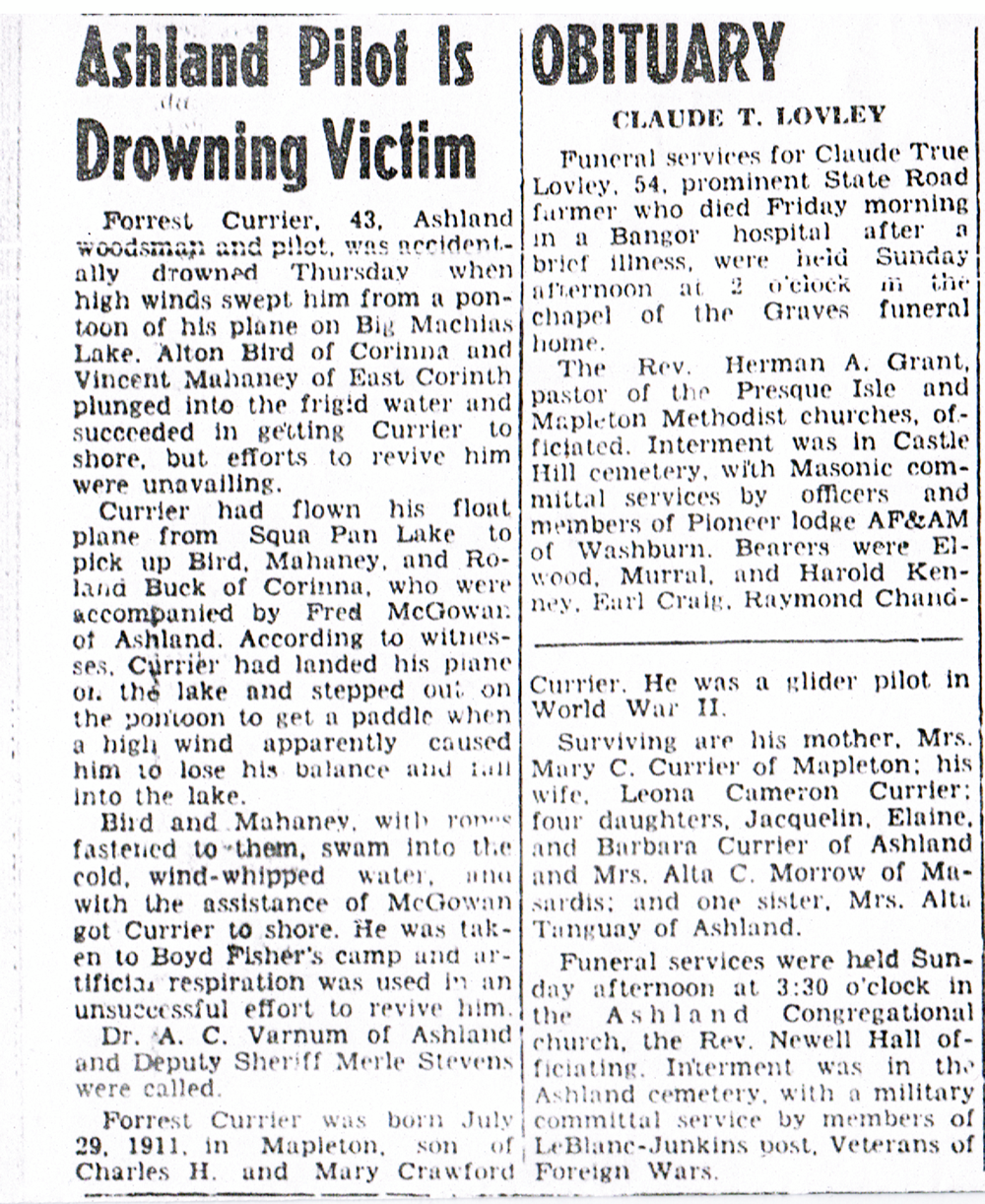

It might be for this reason that a surviving photograph of Fod, taken sometime in the early 1930s, shows a lanky and oddly intense young man who doesn't seem to appreciate having his picture taken sitting on the running board of his Ford roadster.

(That car turns up in several other old family photos, but they're glued into the album, so I couldn't get scans of them. It seems to have been a fixture around the family for quite some time.)

Fod had another vocation besides farming, though, one which runs like a bright thread through a lot of my family history on both sides through most of the twentieth century. He was a pilot, one of the generation of fliers who came of age just after Charles Lindbergh's famous 1927 flight to Paris--in other words, right at the time when aviation in America was really coming into its own.

For such a small town, Ashland had a fairly strong flying community in the golden age of civil aviation. The town was one of the gateways to Maine's north woods, and it didn't take long for a generation of woodsmen to realize that flying was the quickest and easiest way to get from their remote hometown not only to the big cities, but also to the even remoter parts of the state where the best hunting and fishing could be had. Bush piloting became a significant sideline, if not a main occupation, for a fair few adventurous County men, and Fod Currier made a name for himself as one of them.

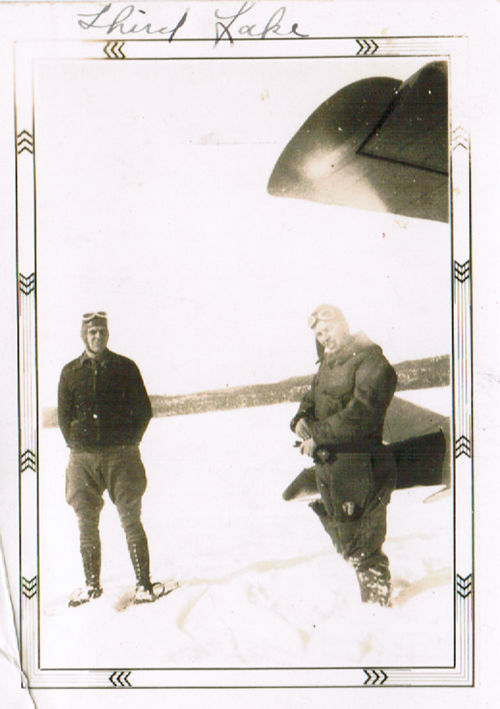

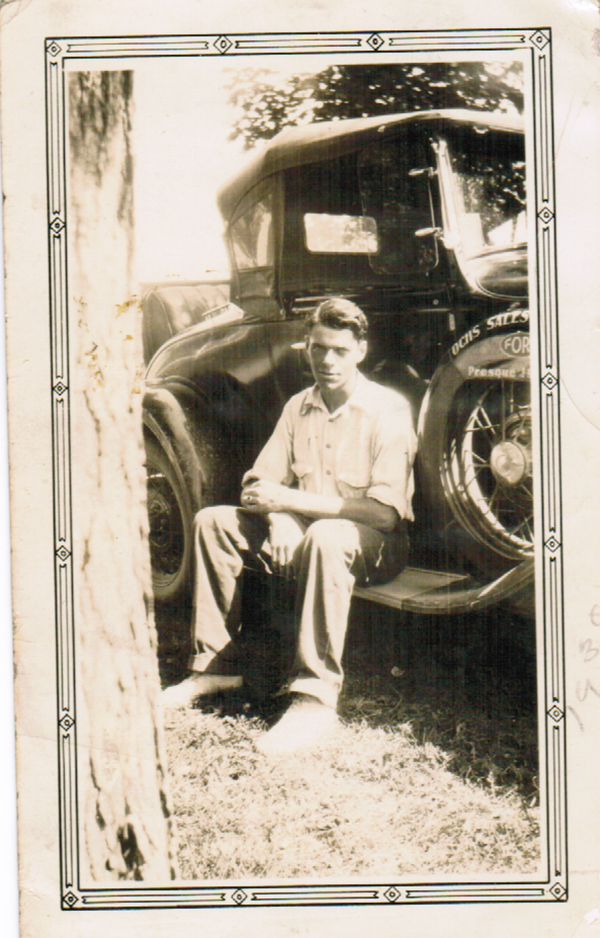

Here he is (on the left) in an undated photo with an unknown other man and a bit of an airplane. Both men are dressed in typical flying clothes of the period. According to the caption, they're at Third Lake. There are several lakes by that name in Maine, and there's no indication on the photo which one, but it's most likely to have been the one up near Eagle Lake, north of Ashland. Since it's pretty much all woods up there, the lakes make for the most convenient places for bush pilots to operate from--on wheels or skis when the lakes are frozen over, and on floats the rest of the time.

In the days when pilots unironically dressed like that, aviation was a dangerous business, and one day in 1937, Fod experienced that firsthand. According to an article in the Presque Isle Star-Herald (the closest thing Ashland had to a local newspaper), Fod was flying with two of his friends when their aircraft suffered a control failure of some kind. He tried to put the plane down on one of the aforementioned frozen lakes, but it was spring and the ice was rotten. The nose-mounted engine, the heaviest part of the plane, broke through the ice at touchdown. Fod and his passengers made it out of the cockpit and climbed to the tail, but the plane didn't float for long.

One of the passengers couldn't swim and disappeared immediately when the plane sank. The other and Fod made separate bids for land. People on shore had seen them go down and were trying to reach them, but conditions on the lake were as bad as they could be--the ice was too rotten to walk on, but too solid to put a boat through. It also made swimming almost impossible. To make any headway, a swimmer would have to break up the ice ahead by hand, swim forward a foot or two, break some more ice, and so on. The Star-Herald account says it took Fod an hour to reach a position where the would-be rescuers could reach him and drag him out of the lake by that method.

An hour in a lake so cold it still had ice on top, alternately smashing said ice with his bare hands and inching forward to smash some more. Fully clothed. Fod was 26 at the time and must have been as strong as an ox. When they dragged him from the lake, his hands were cut to ribbons by the ice and his neck was burned from the gasoline slick that had spread from the sunken airplane. The report doesn't mention it, but we can assume he was also exhausted and significantly hypothermic.

He was too busy fighting for his life to keep track of his other passenger, the one who hadn't gone down with the plane, but whatever became of him, he never made it to shore. At the time the Star-Herald article went to press, the second man's body hadn't been found.

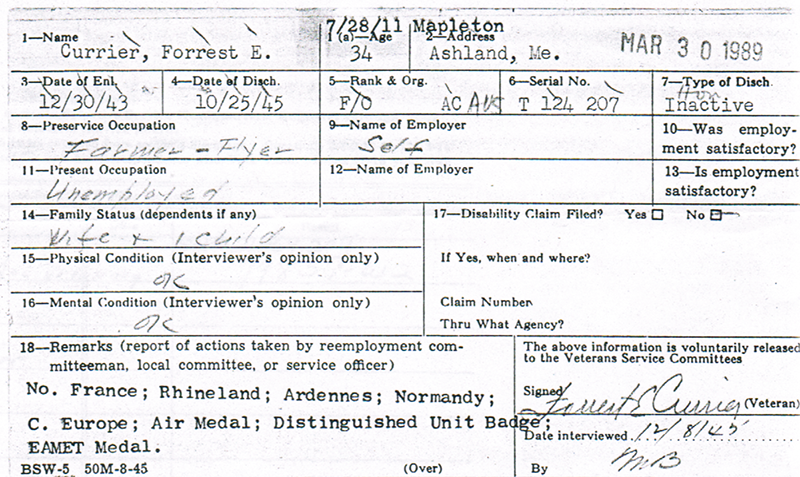

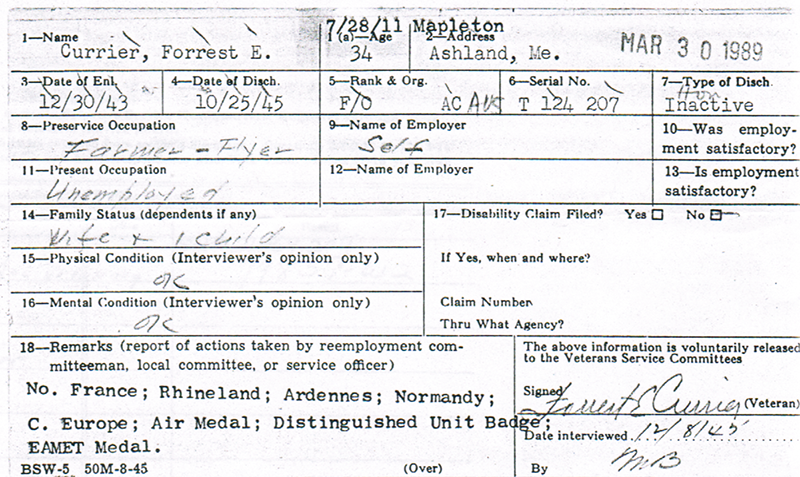

When my mother, who grew up in Ashland and neighboring Masardis, was a little girl in the 1950s and early '60s, she heard a rumor that Fod was convicted of manslaughter in the matter of his friends' deaths, and that the judge gave him the choice of going to prison or joining the Army. It wasn't true. The crash happened in 1937, but I have a copy of his Army discharge record. It shows that he joined on December 30, 1943. Whatever motivated him to enlist at the ripe old age of 32, it wasn't a criminal penalty for something that happened when he was 26. As far as we've ever been able to find out, he was never charged with any crime in connection with the crash. That's just how small-town scuttlebutt goes.

Unfortunately, the record of his Army service is extremely skeletal. The Department of the Army responded to a request for his service records with an apologetic letter explaining that they had been destroyed in an accidental fire, which is the United States government's way of denying any request for information which it finds inconvenient to answer. All we have is his discharge card, which contains the bare essentials of his not-quite-two-year career.

Still, that's something. From it, we can see enough to know, with a little context, that Fod Currier's wartime service was anything but uneventful.

The first clue is his rank: Flight Officer. Flight Officers were a thing that only existed for a handful of years during and immediately after the war. They were a special class of pilot, one that should have been made up of commissioned officers, except that the Army had already hit its legally allowed maximum number of commissioned officers. Instead, the rank of Flight Officer, a specialized type of warrant officer, was created in order to give these special pilots something akin to officer standing, which they would need because of the very particular type of aircraft they flew.

Flight Officers were glider pilots. Their job was to guide unpowered aircraft loaded with airborne infantrymen and their equipment--stuff that was too big and heavy to be dropped by parachute--to controlled crash landings behind enemy lines. As you might imagine, this was a one-way trip. Once they were on the ground, assuming they survived the landing, glider pilots were under orders to rendezvous and wait to be picked up and returned to base--but while trying to find their way to the rendezvous point, and while waiting, they were just as subject to attack by the enemy as anybody else in a U.S. Army uniform. They had instructions to stay out of the thickest fighting, as it was not their specialty, but they were absolutely not noncombatants. Between that and the hazards of their actual mission, they had a not-inconsequential loss rate.

As a member of the 53rd Troop Carrier Squadron, Fod belonged to a unit that had carried out glider operations in Sicily as part of Operation Husky; but that was in the summer of 1943, before he enlisted. Based on his date of enlistment, he would have completed training just in time to be sent with the 53rd to England, as part of the big spring 1944 build-up for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of western Europe.

From there, the bare few words typed in the Remarks box on his discharge record tell a very big story. No. France, Normandy. The airborne landings in support of the Overlord landings on D-Day. Paratroopers and glider forces hit targets inland of the invasion beaches in the wee hours of June 6, 1944, before the landing craft started coming ashore.

Ardennes. A forest in Belgium. After Allied forces drove them out of northern France in the summer and fall of 1944, German forces staged a massive counterattack, their last significant offensive of the war, in winter 1944–45--an offensive now known as the Battle of the Bulge. 53rd TCS gliders carried reinforcements and supplies to the besieged Allied units near the Belgian town of Bastogne, which is famous today as the crux of the battle.

Rhineland, C. Europe. The glider forces' last big operation in the European Theater. 53rd TCS gliders carried the 17th Airborne across the Rhine River into Germany itself in March of 1945, weeks before the war in Europe finally came to an end.

Based on this list, the only major airborne operation of the campaign in northern Europe that Fod missed was Operation Market Garden, which was a huge, complicated, ultimately unsuccessful joint British-American airborne and ground assault on a series of strategic bridges in the Netherlands. It may have been lucky for him that he did miss this one, since the ground forces that were supposed to support and ultimately relieve the airborne at Market Garden's farthest point, the bridge at Arnhem, weren't able to get through (hence the title of journalist Cornelius Ryan's book and the subsequent motion picture about the battle, A Bridge Too Far).

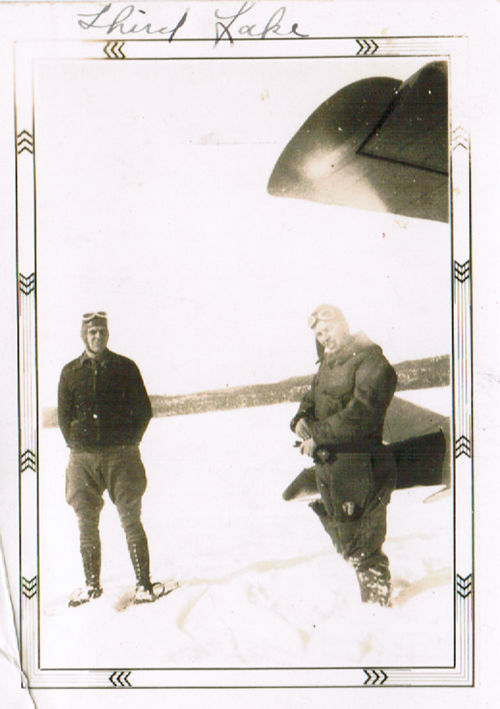

It's unclear why Fod wasn't part of Market Garden, but he might have been back in the United States at the time of the operation, in late September of 1944. The evidence suggesting this possibility is a single surviving photograph:

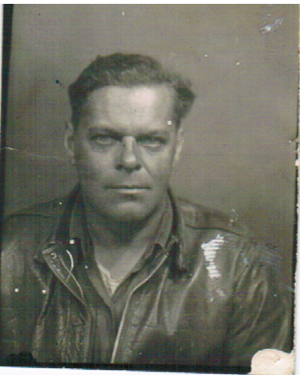

A note on the back of this picture (which I didn't have the presence of mind to scan while I had it) says it shows Fod home "on furlough from Stuttgart Ark[ansas]" in October, but the year is partially torn off. He was only in the Army for two Octobers, 1944 and '45, and he was discharged on October 25 of the latter year. It seems strange that he would have been on furlough in the same month during which he was released outright from the Army, so it seems more likely that the picture was taken in October 1944. Given transit time to and from Europe at the time, that suggests he could have been away at the time of Market Garden, then returned to duty in time to fly the missions supporting the 101st Airborne in Bastogne that December.

Fod survived the war unscathed, at least physically. As noted above, he left the Army in October 1945 and returned home to Ashland, his wife, and his 12-year-old daughter Alta, who was named after his sister. He resumed his life as a woodsman and bush pilot, was widowed, remarried, and had three more daughters with his second wife. He was well-known and respected in the community, belonged to the VFW and the Glider Pilots' Association, and, like a lot of veterans, never talked about the war.

A photo from that period, which looks from its framing like it might have been part of an official credential of some kind, shows an older, more weathered Fod--even though he can only have been around 40--and though there's a hint of wry humor in his expression, those eyes have seen some shit.

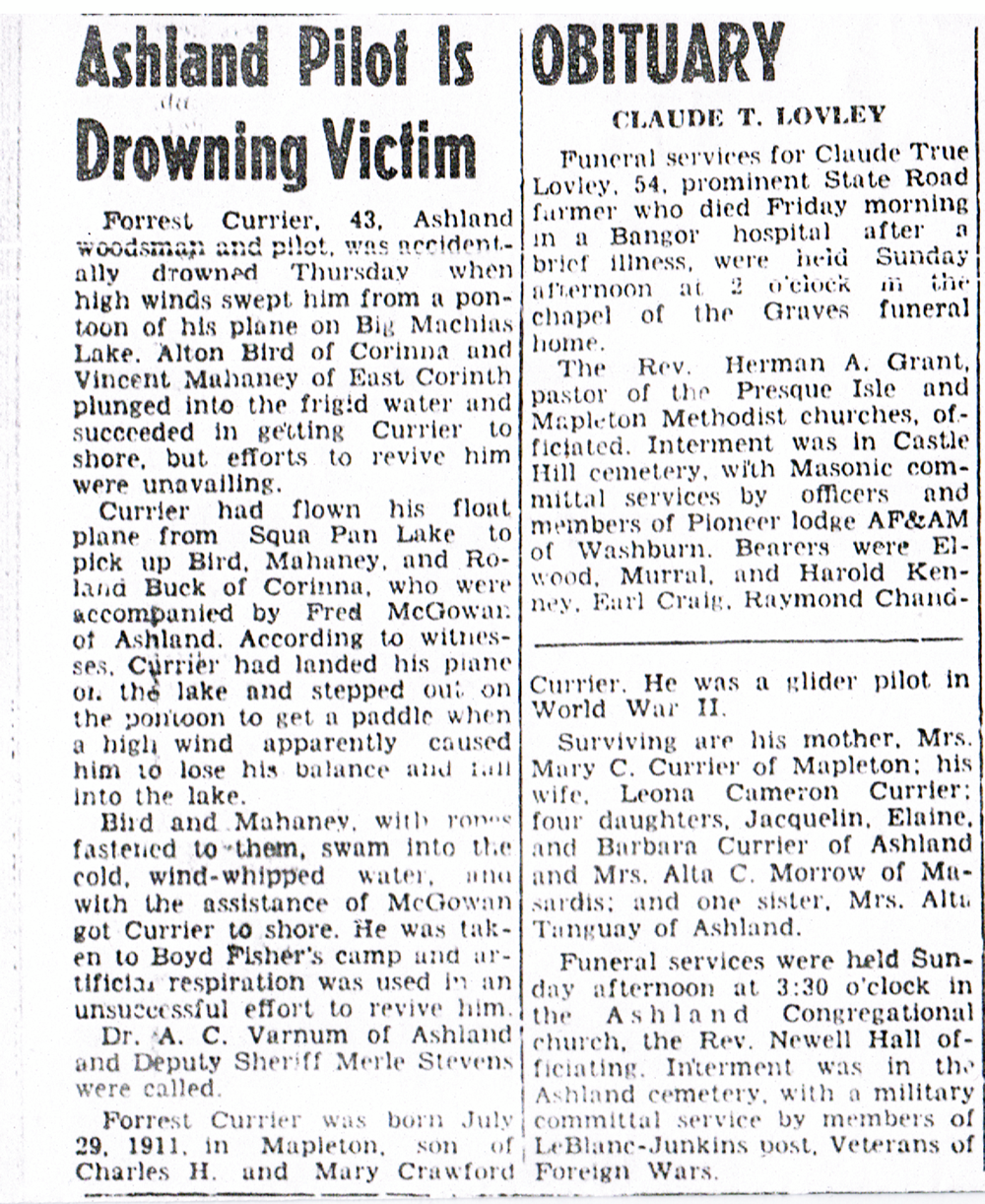

Lingering wartime trauma notwithstanding, in November of 1954 things were going pretty well for Fod Currier. He was 43 years old, a well-regarded flier and guide, not lacking for work, his second family was doing well, and he had two grandchildren by his eldest daughter, Alta, with a third on the way. She was married to a fellow Ashland-area bush pilot, Clair Moreau, and so still close to hand, still a part of his world.

One day, when he had nothing much else going on, he volunteered to substitute for another colleague who couldn't make an arranged trip to take four men out to Big Machias Lake (which, in the usual way of Maine place names, is in the woods east of Ashland and absolutely nowhere near the coastal city of Machias). No accounts of the trip itself survive, but we can probably assume that the five men in the plane made for an upbeat party. It was a recreational trip, after all, and it was a holiday that would have had significance for Fod: November 11, Veterans Day.

In those days, a lot of pilots operating float planes on the lakes in the Maine woods preferred not to taxi under power to shore after landing on the water. Instead, they would shut down, get out onto one of the pontoons with a paddle, and paddle the plane to shore like a particularly ungainly outrigger canoe. Upon landing at Big Machias Lake, Fod climbed down to the pontoon, made ready to commence paddling... and fell into the lake. A subsequent Star-Herald article attributes the fall to "high winds", but later qualifies that explanation with "apparently". It seems no one really knows why or how he fell.

All that's known for certain is that he did fall, and although his passengers jumped in after him and got him to shore, by the time they did, he was dead. Killed in an accident eerily like the one he had so incredibly escaped 16 years--and a world war--before.

I'm not completely sure why I decided to tell you about Fod tonight. Partly it's the timing--the gap between V-E Day and Memorial Day, when a historically minded person's thoughts naturally turn to those we know who have served. Not that I can claim to "know" Forrest Currier; he died 19 years before I was born. I do have a personal connection with him, though: He was my great-grandfather. His eldest daughter Alta, who married one of his colleagues, was my mother's mother. Mom was also too young to know him--born in 1953, she was less than two years old when he took that last flight to Big Machias Lake--but she grew up hearing stories about him from her relatives on her mother's side.

The other day, having promised to do so for years, I drove my mother on a sort of pilgrimage to all the various cemeteries scattered around eastern Aroostook County where relatives of hers are buried. It was a long day--270 miles, mostly on backcountry roads, to five separate cemeteries in four different towns. One of them was the little cemetery in Oxbow, the now-unorganized township where my father's parents lived when I was a kid, and where my grandmother is now buried. The others range all over the vicinity of Ashland and Masardis.

The most picturesque of the five we saw was the Protestant cemetery in Ashland, which is on a hill in the woods outside of town. The terrain makes it kind of an awkward place to put a graveyard, and renders any kind of reference system for finding individual graves almost impossible, but with the help of a kindly chap we ran into at the town office while seeking directions, we tracked down her Grampy Fod and Grammie Leona's grave. It's near the top of the hill, backed by a lilac bush which must be lovely at the time of year when it's in bloom.

Notice that someone chose to decorate Fod's side of the stone with an image of a float plane coming in for a landing on a lake. That seems... a trifle on the nose to me, but when I mentioned it to Mother, she shrugged and said, "It was what he loved to do."

Since he was a war veteran, his side of the grave also has a footstone provided by the VA with information about his service.

I've been thinking off and on about Fod ever since. Maybe in part because we came so close to not finding his grave, maybe just because I'm getting to that age when ancestors from before our own living memory become important. Or because I could theoretically have known him if he hadn't died young--a characteristic he coincidentally shares with his daughter, my "other" grandmother, who likewise died in a strange accident long before I was born. I might tell you about her another time. She's been on my mind lately too.

So that's the story. It doesn't really go anywhere or signify anything, but it's all I can piece together now about the life of my great-grandfather Forrest, my mother's Grampy Fod--a strong and lucky man whose luck and strength both ran out on a cold and lonely lake one long-ago Veterans Day.

--G.

-><-

Benjamin D. Hutchins, Co-Founder, Editor-in-Chief, & Forum Mod

Eyrie Productions, Unlimited http://www.eyrie-productions.com/

zgryphon at that email service Google has

Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam.

Printer-friendly copy

Printer-friendly copy