LAST EDITED ON Apr-06-17 AT 06:14 PM (EDT)

No, not the tank. The other other M1.

So, it's the late 1930s, and after literally a decade of faffing around, the United States Army has finally standardized on the Rifle, Caliber .30, M1, which everyone calls the Garand rifle after its inventor. There have been a few hitches, but the Garand is finally in mass production and making its way out to units. At last, the U.S. Army has, to coin a phrase, perhaps not the rifle it needs so much as the rifle it deserves. And with the probable exception of Mr. John Pedersen, everybody's happy.

(puts hand to earpiece) I'm... I'm being told that not everybody is happy.

The problem should be fairly obvious: the M1 Garand rifle is enormous. With its full-length hardwood furniture, its need to withstand the massive .30-'06 cartridge, and all the trimmings, it weighs between 9½ and 11½ pounds, and that doesn't count the ammunition. That is one to three pounds heavier than the bolt-action M1903 Springfield rifle it replaced. It's only slightly longer than the M1903, but bulkier, with its girthy stock designed to enclose the gas system and its internal double-stack magazine.

If you're a generic infantryman, which is to say carrying a large rifle is literally your only function, that's not such a big deal. It's not like you need your hands free to do anything else; you are essentially a transportation and fire control system for the rifle. Sure, it's heavy, and bulky, and more powerful than you are ever going to need, but it's not more than you can deal with, and the Army does not care if it inconveniences you.

Suppose you have some other job, though. Operating an artillery piece, say, or carrying the radio (which in those days was a massive backpack-mounted affair that basically needed three people to use, one to carry it, one to actually operate it, and one to talk over it), or having a bazooka, or driving a truck, or—well, basically any military task that doesn't involve just carrying a big ol' rifle around.

As it turns out, you, my friend, are going to find "the greatest battle implement ever devised" to be a massive pain in the ass. It's heavy, it's awkward to carry, it gets snagged on everything, it occasionally bashes you in the head or falls off your shoulder if you're trying to carry it slung with all the other junk you have to worry about, and you can't shake the suspicion that if you ever actually have to fight anybody in your job, a 3½-foot-long rifle that can shoot a mile and a half is going to be about as much practical help as a pine log.

Complaints about the unsuitability of the Garand for support personnel arrived at the Ordnance Department just about as fast as the Garand arrived in the hands of support personnel. Astonishingly, the Ordnance Department listened to them.

The idea of a carbine—a shorter, handier rifle than the one issued to the general infantry—was hardly new in 1938. Cavalry had had them for generations by that point, and they had filtered off to other non-infantry units in the general course of things. The concept had gone by the wayside in the US forces by the 1930s, though; the last cavalry carbine adopted, as far as I can tell, was the Springfield M1899, a slightly shorter version of the M1892 "Krag-Jørgensen" rifle. There weren't carbine versions of the M1903 Springfield or M1917 Enfield, possibly because they were already considered short rifles (in the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield sense).

Bowing to the pressure from support and second-line troops for some weapon that was lighter and handier than the M1, but of more use against a possible encroaching enemy than the M1911A1 pistol, the Ordnance Department put out feelers for a new, lightweight carbine to fill that gap.

Meanwhile, over at Winchester, a team of engineers was working on a rifle they called, with cheerful confidence bordering on outright hubris, the M2—the idea being that they thought they could persuade the Army to replace the M1 with it a whole three years into production (or, failing that, get the Marines, who hadn't yet adopted the M1, to take it instead). That didn't work, but the request for carbine submissions came in at around the same time. One of the things that was already a priority for the M2 project was to make the rifle lighter than the M1, so it seemed like a logical direction to go in so as not to waste all the time and money put into the M2.

One of the M2's designers was a man called David Marshall Williams, known to his friends as Marsh and to history—spoiler alert—as "Carbine" Williams. Williams is a fairly heavily mythologized figure nowadays; his life story was colorful enough that Hollywood, in its grand tradition, felt the need to make it more colorful by making a movie after the war in which Williams (played by Jimmy Stewart) single-handedly invents the carbine and saves the free world.

I would have thought his actual story, which involved being thrown out of the Navy at 17 for having lied about his age when he enlisted at 16, then being thrown out of military school for stealing a bunch of rifles, then going to prison for the murder of a sheriff's deputy while bootlegging liquor, then becoming such a well-regarded machinist in prison that he became the gunsmith to the prison's guards, then started designing and building prototype semi-automatic rifles while in prison for murder, and then having his sentence commuted because his skills as an arms designers were considered Valuable to the Country would have been colorful enough without revamping the story to give him sole credit for what had been a team effort, but don't go by me.

Seriously, that all happened.

Anyway! The key innovation Williams brought to the M2 project, which was carried into the new carbine project that followed it, really was his invention: a short-stroke gas piston system. As opposed to a long-stroke gas system like the one in the Garand, where the gas piston travels the full length of the operating stroke along with the bolt, bolt carrier, and so on, the piston in a short-stroke (also known as "gas tappet") system isn't attached to the rest of the system. It moves a short way, strikes the operating rod, and stops, imparting sufficient kinetic energy for the action to work without its continued involvement. This reduces the amount of mass that's moving around inside the rifle during each stroke, and the volume of space that has hot gas (and the potential for residue buildup) in it. Gas tappet actions can be made quite compact, and indeed, the new carbine's was.

Other elements of the carbine's design were taken straight from the Garand, only at a smaller scale: the operating handle is eerily similar, and the bolt uses a similar rotating lockup action with the operating rod on the right-hand side. They're both semiautomatic-only, though where the Garand has its internal magazine, the carbine was designed from the start to use a detachable box magazine. Instead of the massively overpowered .30-'06 cartridge, Winchester coupled the Williams gas system and Garand-like bolt mechanics with a new non-bottlenecked cartridge derived from one it already had in its repertoire.

Remember in the entry on the Remington Model 8 I mentioned that before the Model 8, attempts at self-loading rifles had used "compromise" cartridges that were underpowered by comparison and not very popular? Well, .32 Winchester Self-Loading was one of those. By scaling it down very slightly and using modern, more powerful propellants, Winchester developed what became known as the .30 Carbine cartridge, which was about a third as powerful as .30-'06, but still hit harder than the .45 ACP cartridge used by the M1911A1 and the Army's officially adopted submachine gun of the time, the Thompson.

Here's a photo of a .30 Carbine cartridge with a .30-'06 dummy round (I don't have any real .30-'06 ammunition at the moment) for comparison.

Using that cartridge, the carbine's original magazines could hold 15 rounds in a slimmer and lighter package than the Garand's eight.¹

With the design and the cartridge completed, Winchester's new carbine was everything the Army's support troops were looking for: smaller, lighter, much handier, and far less punishing to the shooter than the Garand, with a larger ammunition capacity and chambered for a cartridge a man could carry a fair amount of without getting bogged down.

To great anticipation, it was adopted as U.S. Carbine, Caliber .30, M1 in October of 1941—just in time for the US entry into World War II two months later. A folding-stock variant for paratroopers, the M1A1, would follow shortly. Wartime needs further led to the development of the M2 (actual Army designation, not to be confused with Winchester's codename for the development rifle that preceded it), a selective-fire M1, and the M3, which is an M1 or M2 equipped with a hilariously primitive infrared sniper scope. Carbines of the M1 family remained in US service until the early 1970s and can still be found in other forces (and the hands of some police agencies) today.

The M1 carbine is a controversial little so-and-so, even today. Some participants in the war thought they were the greatest thing since sliced bread. More powerful than the Thompson gun, but much lighter and with more compact ammunition, it provided significant firepower to personnel who otherwise would've had only handguns to defend themselves. On the other hand, you'll find other accounts deriding the .30 Carbine cartridge as wimpy to the point of uselessness and the carbine itself as flimsy and inaccurate.

It's also proven hard to categorize, which annoys some military history writers. Is it an assault rifle? Well, no; .30 Carbine is more powerful than comparable pistol ammunition, but not enough so as to be a convincing intermediate rifle round (and besides, only the M2 version is selective-fire). Is it a submachine gun? Well, again, no; by definition, an SMG is chambered for a pistol cartridge, and .30 Carbine isn't that (although a few handguns would later be chambered in it for novelty value). Whatever its detractors may want to believe, the numbers don't lie: a 110-grain bullet doing around 2,000 feet per second is no slouch. So it's in this weird grey area, neither one thing or really another, and that makes some people uncomfortable. Even makes a few of them angry.

Until recently, that is. Of late, an ostensibly newfangled category of firearm into which the M1 (and more particularly the M2) retroactively fits quite neatly has become a buzzword among the Tactical Timmies of the world: "PDW", or Personal Defense Weapon, the new jargon for a weapon that's more powerful than a pistol, but not as powerful as a rifle (specifically, not as powerful as an M4 carbine, is the usual metric), intended for the use of communications personnel, truck drivers, artillerists, etc. etc. who may need does this sound at all familiar? Once again there is nothing new under the sun.

Let's have a closer look at the specific example we're dealing with here today, because it has some stories to tell.

What we have here is a regular old, semi-auto, fixed-stock M1 carbine. It's shown here with the sling and magazine it would have had when originally issued; they're modern reproductions, but made to the GI spec. (In the top photo above, it's fitted with the magazine it came with when I bought it, which is actually a 30-round magazine for an M2.)

Note the chamber marking. Since the difference between the M1 and M2 was literally just some added widgets in the trigger mechanism to make it select-fire, M1s could be (and many were) converted into M2s in the field. If that was done, the standard procedure was for the unit armorer to overstrike a "2" on the M1 marking shown here. And here's an interesting quirk of law: carbines marked M2, whether factory original or overstamped, are machine guns in the eyes of the ATF, even if they've been reconverted back to semi-auto at some later point. Converted M1s that weren't overstamped, on the other hand, are only NFA machine guns if they still have the full-auto trigger conversion. Put the original semi-auto trigger hardware back, and they magically become legal for ordinary scrubs again.

I mention this because: see that cut-away bit of the stock on the left side of the receiver there? That's where the selector lever would be if this were an M2. Now, this M1 has been through the wringer more than once in its life, and I've read that it was arsenal policy for M1s needing a new stock to get an M2 stock after the M2 was adopted, to simplify supply (because armorers would then only need the version with the selector cutout). That may be all we're looking at here; or it may be that at some point in its long, long life, this carbine was converted to an M2 but not overstruck, and then converted back again at some later date. There's no telling.

It's also impossible to say who made this carbine originally, at least completely. During World War II, some six and a half million carbines of the M1 family were produced, the vast majority of them—oddly—not by Winchester. The principal contractor for carbine production was Inland Manufacturing, a division of General Motors, but other GM divisions (Saginaw Transmission, for example) also got into the act. Other carbines were supplied by International Business Machines, Underwood (the typewriter company), and—I promise I am not making this up—Rock-Ola, the jukebox manufacturer.

The thing is, not all the parts in any given issued carbine necessarily came from the same supplier. That is, after all, the beauty of interchangeable parts. Rock-Ola, for instance, routinely made the wooden furniture for other contractors, and subcontracted out some of the smaller metal bits in its own production runs.

Thus, this particular carbine's barrel is marked as having been made by Inland:

It's hard to read, because it was tricky to photograph roll stamping on a round part, but it says

INLAND MFG. CO

GENERAL MOTORS

7-43

However, that doesn't necessarily mean the receiver is also an Inland, nor any of the other parts. They probably are, Inland made by far the largest number of carbines, but unless they're marked someplace that's currently hidden inside the stock, there's no way of knowing. The only other obvious maker's mark is on the front barrel band:

According to a War Department memo available from the Civilian Marksmanship Program, the "SI" mark indicates that that particular part was made by a subcontractor called Simpro Manufacturing. I've never heard of them, and a web search turns up a Norwegian company that makes electronics and one in New Zealand that appears to be in the forklift business. Neither is likely to be the company that was making bits of American rifles in the 1940s, so I have no further information.

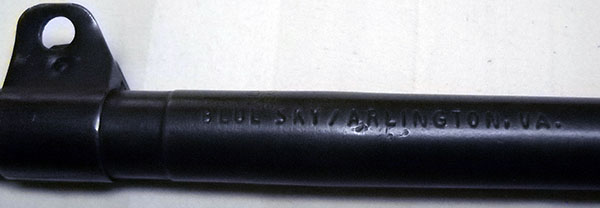

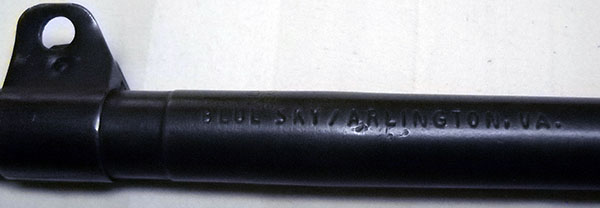

Another mark on this carbine's barrel gives a clue to some of the specifics of its long and eventful career.

That is an importer's mark, showing that this carbine was imported by a company called Blue Sky based in Arlington, Virginia. Which seems odd, since the M1 is an American military firearm from a time when all such items were universally made in the USA. The thing is that, as I mentioned earlier, the various contractors made literally millions of these things. After the end of the war, the US Army didn't need all of them, but there were a lot of armed forces elsewhere in the world that did. Much as the Soviets lavished military hardware on their fraternal socialist comrades, the US defense establishment of the 1950s and '60s would happily ship crates and crates of outmoded gear to the attention of anyone they thought might provide useful support in the Fight Against Communism.

When, in turn, those organizations were also finished with the by-now-well-traveled carbines, there was really only one market in the world to sell them off to, and that was back in the USA. Blue Sky was an organization set up to handle the repatriation of these former military aid assets from the places they were sent to—particularly, based on what I've been able to dig up online, the Republic of Korea, which got something like a quarter of the world's M1 carbines after World War II and has since sent rather a lot of them back.

While we're out here on the barrel, note one of the carbine's most hilarious features:

... it has a bayonet lug. This was supposedly added by popular demand toward the end of World War II. I cannot imagine why. I'm not even sure I believe that was really the reason.

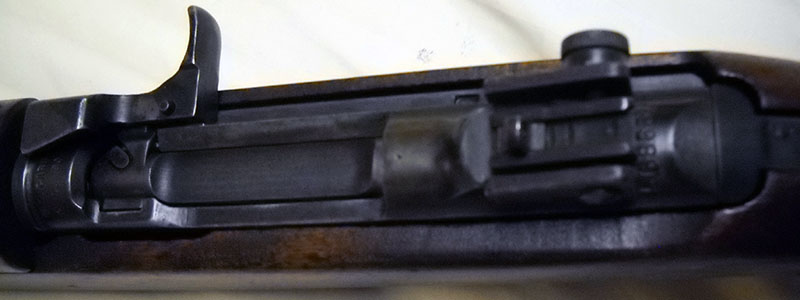

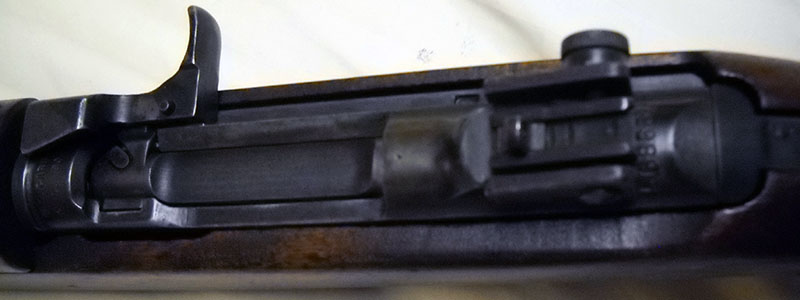

Turning our attention to the carbine's action, we can see the resemblance to the M1 rifle in its mechanics:

Yup, that's an M1 operating handle, all right.

In this view we can get a better look at the locking lugs on the rotating bolt (here in the closed and locked position) as well as one of the action's quirkier features. The carbine's action doesn't automatically lock open on an empty magazine, but it can be locked open using that little button on the operating handle. When the bolt is drawn fully to the rear, pressing that button engages the notch you can see machined into the back of the right-hand receiver rail in the photo of the full action above, locking it in place. Pulling a little farther back and letting go drops the bolt forward again.

(Interestingly, this particular one will also do that "bolt hangs up on magazine follower" thing the Garand will do. I think the follower may even be designed to encourage it, but it's not very reliable. M1 carbine thumb is probably not as bad as full-size M1 rifle thumb, but I still don't want it. Then again, you don't have to stick your thumb in there to load the carbine, unlke the Garand. GI .30 Carbine ammunition did come on stripper clips, weirdly enough, but they were to make loading the magazines faster, not for putting in the gun.)

Another interesting detail of the carbine's design is the way the sling is retained. At the front, it's just snapped in place around a standard rectangular ring using the kind of snap button closure you see on a lot of WWII American canvas gear, but at the back, it's secured in a slot in the buttstock with a sliding buckle. What's interesting about this is that the pinion in the slot isn't built in.

That object you see in the slot there, with the sling passing around it, is an oil bottle—notice the knurled bit at the top, which unscrews and has a metal prong on it that serves as a dropper. That's a pretty clever way of eliminating two manufacturing steps and an extra part in the manufacture of the stock; otherwise, there would need to be a separate compartment for the oiler and either another sling swivel, or a metal pin somehow fixed in that slot to serve the same purpose. (I say "somehow fixed" because presumably the designers wouldn't have wanted it to be removable if it didn't serve some other purpose.)

It does mean you have to unsling the rifle to get the oiler out and use it, but since soldiers doing maintenance are generally not in a hurry, that's not really an issue.

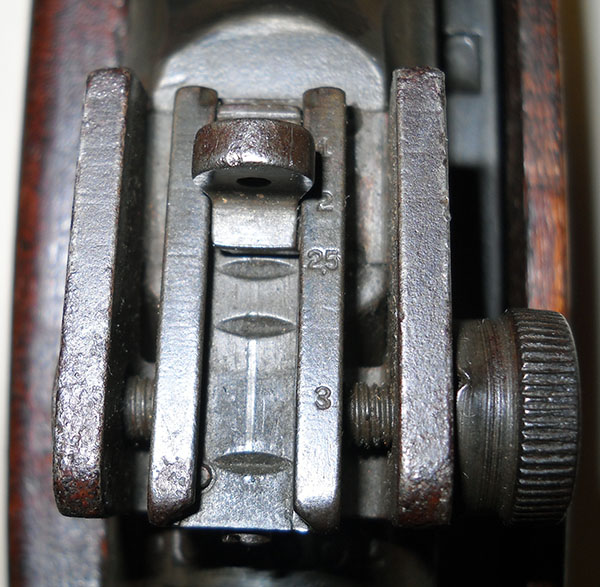

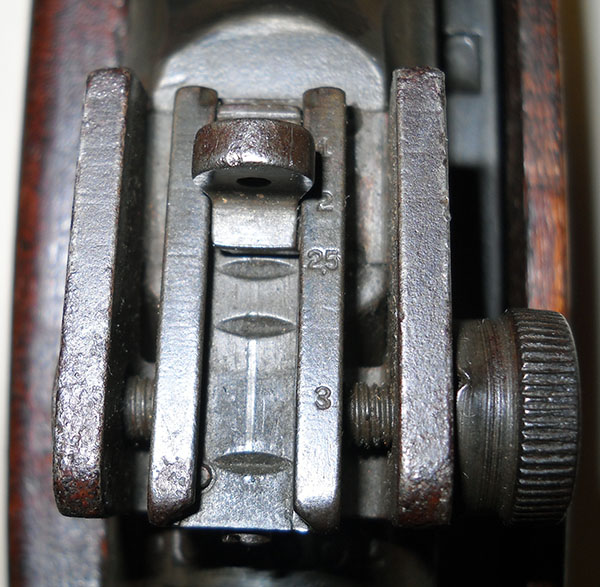

The carbine's rear sight is adjustable; the bit with the aperture can be moved along a little ramp to adjust the point of aim for range.

As you see, it's less ambitious than a lot of the sights on big-boy rifles of the time—only goes out to 300 yards—but still, a hundred-yard zero on a little 18-inch-barrelled carbine like this? No wonder people bitched that they were inaccurate. This sight is also adjustable for windage (that is, side-to-side), using the knurled knob on the right to move the sight platform back and forth along the screw you can see running across near the 300-meter marker.

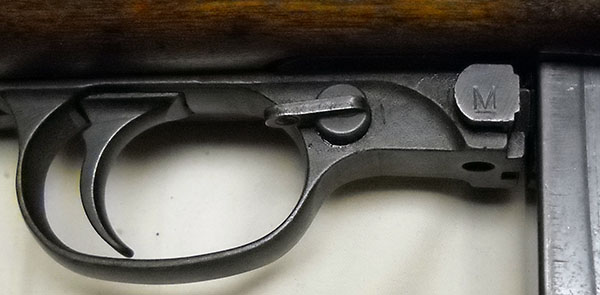

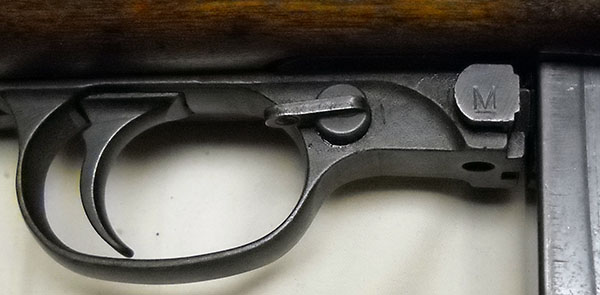

Up on the front of the trigger guard we find the rifle's only two controls besides the bolt handle:

The button farther forward, helpfully marked M, is the magazine release. The switch behind it is the safety, which is shown here in the ON position. It's turned off by rotating it 90 degrees:

On the early production M1s, the safety was a cross-bolt button instead. You'd press it on the left side (so that it stuck out the right) to engage the safety, and press it back in on the right (so that it stuck out the left) to turn it off.

Can you guess why they changed it?

If you said "because dudes were going for their safety buttons without looking and dropping their magazines on the ground instead," you win!

This was quietly changed a few months into production, without bothering to increment any version numbers, and the existing cross-bolt button versions were swapped out for the rotating switch when the rifles came in for their 30,000-mile servicings. Shhh. We never did that. It never happened.

The magazine catch itself was also modified a short way into the war. The original M1 magazines were straight-walled metal boxes that held 15 rounds. When the selective-fire M2 was introduced, it came with a curved magazine holding twice as much ammunition (as seen in the first photo above).

Unfortunately, that meant it was twice as heavy when fully loaded, and the original M1 magazine catch, which only engaged a couple of small metal nubs on the back of the magazine, wasn't strong enough to retain it.

The fix was to switch out the original magazine latch for one with an arm over on the lefthand side, engaging with a third, slightly larger nub on the corner of the magazine.

Seems like a small change, but it did the trick. Best of all, it didn't render the old magazines unusable, which is not always a detail military armorers get right when they make a change like that. The magazine catch change was, like the safety swap, made standard as something to be changed on the older ones when they came in for service.

And I'll tell you what, I suspect mine was in for service quite a bit. There's evidence all over the stock of some fairly major repairs made somewhere along the line. The biggest one is up in front of the magazine well:

Check that out. That is a big old multi-angle fracture, with some material outright missing, pinned back together with several brass pins that were then polished off and smoothed down. I'm no expert, but that looks like the kind of break that would happen if someone deliberately tried to break the rifle, say by swinging it by the barrel against a tree.

The rear of the stock is cracked and pinned too, right at the tang on the back of the receiver:

When I was a kid, my uncle was in a bad skydiving accident, and they had to nail one of his ankles back together with titanium pins. This rifle reminds me of that.

That's both the beauty and the danger of collecting old firearms like this. They'll have stories to tell, but they can only partially tell them. The rest is for us to piece together, with detective work, intuition, educated guesswork, and wild-ass speculation. What the heck happened to this old carbine? Where and when? Was it during its service with American forces in the war (which it certainly could have seen, having been produced in the summer of '43, assuming the rest of it is contemporaneous with that barrel)? While it was bulwarking against Communism in Korea? After being reimported and sold to gods know who back in the States?

There's just no telling, although I would think surely a military armorer would just have replaced a stock as badly damaged as that—at least an American one. On the other hand, if it's a civilian repair, it looks to have been pretty handily done. The only really loose part on this rifle is the upper hand guard, which doesn't seem to fit very well or match the grain of the main stock, and so is presumably a later replacement that wasn't fitted very well. The rest of it seems solid. And how come it has an M2 magazine and M2-pattern stock?

I could get it re-stocked; could, in fact, send it off to the CMP's pro shop for a complete overhaul and refinish. New barrel,² new stock, mechanical tune-up, fresh coat of Parkerizing; it'd basically be a whole new carbine when I got it back, for less than a brand new commercial one would cost. I'm not sure I could bring myself to do it, though. It's got so much mystery and character about it as it is.

And yes, there are still brand new commercial M1 (and M1A1) carbines being produced, by several companies. One of them calls itself Inland Manufacturing, but (of course!) has nothing to do with the old GM division that made so many of the wartime carbines. The design has reportedly been altered a bit to simplify production for modern economic sensibilities, but they're still quite expensive for what they are. No new M2s, of course, though there are still some transferable vintage specimens around. (I guess theoretically you could put a vintage M2 conversion kit on a commercial M1 carbine, if the trigger group was not one of the things changed for modern production—then you'd have Manufactured a Machine Gun and the ATF would want to have a word with you.)

--G.

-><-

Benjamin D. Hutchins, Co-Founder, Editor-in-Chief, & Forum Mod

Eyrie Productions, Unlimited http://www.eyrie-productions.com/

zgryphon at that email service Google has

Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam.

¹ Don't mind the two different kinds of fake ammo in the Garand clip there. The red aluminum dummy rounds are expensive enough that I didn't want to spring for eight of them; I didn't realize when I ordered that the orange plastic ones weren't configured with the same faux bullet. The red ones simulate M2 Ball, the regular GI ammo from World War II. The orange ones were sold as .30-'06 dummies, but with those round-nose bullets they look more like .30-'03, the last of the pre-spitzer USGI cartridges.² I think. There is some dispute in online sources as to whether the Blue Sky carbines can legally be re-barrelled, since the "import mark" is on the barrel rather than the receiver where it should ordinarily be. On the other hand, the barrel is not the serialized part, not the "firearm" in legal terms, so was it even technically legal to put the import mark there in the first place? The only way to know for sure would be to send it off and see whether the CMP refused to replace the barrel.

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1 Barrel Update

Barrel Update

Bits & Bobs

Bits & Bobs

RE: The Other M1

RE: The Other M1

Printer-friendly copy

Printer-friendly copy