Originally posted July 15, 2017

This week's Gun of the Week isn't a gun! Except insofar as it is in fact a gun.

What we have here is in fact a flare gun, which is not a weapon but a visual signaling device. It's designed to launch small packets of brightly burning chemicals to an altitude of around 100 feet. That doesn't sound very far, but depending on the terrain, they can be seen for miles around, which is handy if you need to let people know where you are without making a lot of noise. Nowadays, some commercially available aerial flares even have little parachutes in them, which extends the time in which they can be seen from a few seconds to (so I am told) anywhere up to a minute. The classic flare (and the most widely available color today) burns a bright red-orange, but, like fireworks, they can be pretty much any color.

The gun-launched aerial signal flare as we know it today is credited to one Lt. Edward Very, USN, who received a patent for such a device in 1877. Presumably Lt. Very was thinking of the particular need that sailors often have of signaling to people who are not within earshot, especially as radio hadn't been invented yet at that point. United States forces called the launchers Very pistols for decades thereafter, as did some allied forces (the British, for some reason, preferred to spell it Verey). As late as World War II, you can find references in battlefield literature to the use of "Very lights", even though by then they weren't officially called that any more.

Military users of Very flares generally used them for various kinds of announcements and/or to mark locations. To name just a few: Downed aviators used them to attract search-and-rescue personnel. Bomber crews returning to their bases in World War II often had particular sequences of flares they were meant to launch on approach, to alert ground personnel if they had wounded aboard or to give some advance notice of how the operation went. So-called "pathfinder" troops, parachuted into the operational area ahead of major airborne operations, used them to call the inbound main force's attention to their drop zones. And every now and then, someone who didn't have any other weapon handy would fire one at somebody else, or at least threaten to. These things are not meant to be weapons, but they do fire wads of burning gunpowder, perchlorate, metal shavings, and other stuff you don't really want somebody to launch violently at your person.

(In popular culture they probably turn up as improvised weapons more often than they're used for their intended function. James Bond, for instance, blows up a boat with one in From Russia With Love. Setting cultists on fire with the flare gun was by far the most entertaining thing to do in the old first-person shooter Blood, although in fairness that may have more to do with how few really entertaining things there were to do in the old first-person shooter Blood than the actual entertainment value of setting cultists on fire with a flare gun.)

Anyway. What we have here is a United States Mark IV Very pistol of World War I. (It is not to be confused with the British No. 1 Mk IV Verey pistol of similar vintage, nor with the World War II-era U.S. Navy Mk IV signal gun. Ah, military nomenclature.) A bit embarrassingly for the country that invented the Very pistol, this Mk IV was pretty much a straight-up copy of a French design, the Modèle 1917. I haven't found any information so far on why that was specifically the case, but it wouldn't surprise me if it were simply because the U.S. Army was so woefully underprepared to get involved in the Great War that copying the French one was the only way to get enough properly modern ones into service fast enough. Regardless, that's what they did. Let us take a closer look.

Mechanically, there's not a lot to see in the Mk IV. It's a very simple device—similar to any other single-shot pistol or shotgun of its era, really.

Over on the left side, we can see pretty much the only control this thing has, besides the hammer and trigger: the big ol' lever attached to the lock that holds the chamber shut.

Speaking of the hammer and trigger, the Mk IV has a single-action trigger mechanism, just as employed on any number of firearms of its day. In the photo above, it's shown in the fully forward position, as it would be when the pistol had been fired. It also has a half-cock notch, again, typical of its time:

When the hammer is fully cocked, the fixed firing pin is plain to see.

Because of this, the half-cock notch has an important function: The Mk IV should only be opened and loaded with the hammer at half-cock. If closed on a live cartridge with the hammer fully down, it will probably go off. You wouldn't want that. So let's put it back on half-cock and open it up.

The locking lever rotates a full 180°. The notch that it locks into when fully engaged is cleverly cut into the hinge pin that the pistol opens on, a nice way of making one part do two jobs. There is no spring involved in this part; the only spring action in the pistol is in the hammer/trigger group.

Once the lever is fully rotated, the pistol breaks open just like a shotgun.

At this point, just like a shotgun, you would drop a cartridge in there, close the pistol, lock it up, take (rather vague) aim, cock the hammer, and fire.

On the inside, it's just as simple as out.

It's a simple smoothbore, headspaced on the rim of the cartridge. In theory, this would allow for the flares to be of varying lengths, though I don't know if they really were, in practice.

Note that there are no sights of any kind. This device wasn't really meant to be aimed with any precision beyond "point it up in the air", and a flare is probably not an aerodynamically sound projectile anyway, so there's absolutely no need for them—and as you should've noticed by now, there's nothing whatsoever on the Mk IV that there's no need for. For example, there's no safety; undoubtedly deemed superfluous. No one, in the designers' mindset, is ever going to be trying to carry one of these things around loaded. You load it at the moment when you need it—period.

This particular one doesn't even have any mechanism to prevent it from being opened without half-cocking the hammer, although I've seen photos of examples online that have a rather cunning workaround for that problem. The hammers of some Mark IVs, presumably later-production models, have a long spur or hook on the front that overlaps the back of the chamber when the hammer is fully down, so that you physically cannot open it without moving the hammer back out of the way.

(this image grabbed from an ended auction on liveauctioneers.com)

Clever, and almost certainly a running change during manufacture, as it's still labeled Mk IV. (Although you'll note that this one's been rechambered from 25mm to 1"—more on this in a second.) For a change like that, the British would probably have called the version with the hammer hook Mk IV*.

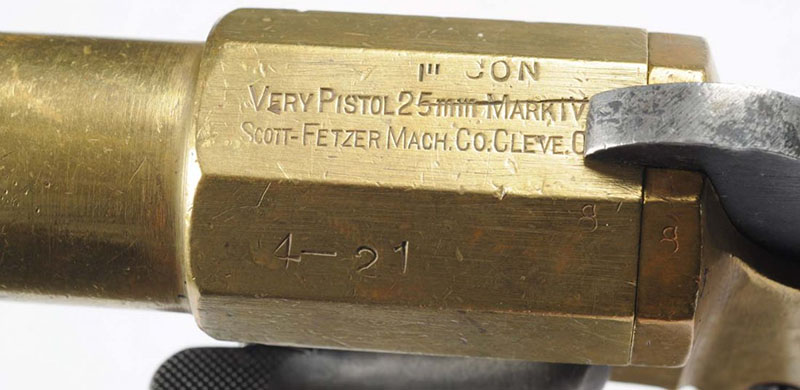

Speaking of labeling, the markings up top are similarly simple and straightforward, telling us what it is, what kind of ammunition it uses, and who made it.

My Mk IV was made by the Scott & Fetzer Machine Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Contracts to build Mk IVs were given to several different American companies in the crash build-up to the war; I've also seen examples online that were made by the A.H. Fox Gun Company of Phildaelphia (then a prominent manufacturer of high-end bespoke shotguns). The Fox ones tend to be more sought-after by collectors these days, on account of the company's more distinguished pedigree, although I am obscurely pleased to see that the Smithsonian's is a Scott & Fetzer.

This particular specimen doesn't have U.S. arsenal acceptance marks, which probably means it was made for the civilian market—odd as it is to think of any production being earmarked for civilian sale during the war; the serial number is low enough that I don't think it was postwar production. All the serial numbers I've seen have started with a single digit, and then either two or three digits after the hyphen. I'm not sure if the prefix digits are batch numbers or what, but I've seen military-issued ones in the 3- and 4- series, which I would assume came after this one, but I don't know for sure. Anyway, this one doesn't seem to have been issued. At least one other example I've seen advertised online bears Canadian broad-arrow marks, indicating purchase and issue by the Canadian Militia (as it was known at the time).

As for caliber, 25mm was the official size of the flares issued by the United States military at the time. The 1"/26.5mm conversions were probably for the Canadians, who at the time would have been using that size (the British standard). I've also seen one that was converted, possibly by a military armorer, to 12 gauge, and heard of adapters one can buy that will convert them to 10 gauge.

I should pause here for a moment and say that these conversions are only safe if used with 12- or 10-gauge flares, which can still be bought, and may or may not be a felony anyway. You do not want to get cute and try to convert one of these things into a tiny shotgun. For one thing, that is very, very illegal. Technically, just by converting one of these into something that can chamber and fire shotgun shells (in the USA), you're making it into an NFA Any Other Weapon. More practically, it's not in any way safe. These things are made of a copper alloy, they can't sustain the kind of pressures modern shotgun ammunition generates.

That brings us to the material involved here, which I think is a bit interesting. You'll see these described online, as indeed mine was in the Simpson Ltd. catalog, as being made of brass, but I think it's more likely to be gunmetal. (Which looks like this and is not bluish-grey, despite the fact that that's the color called gunmetal. Go figure.) Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc; bronze is an alloy of copper and tin. Historically, gunmetal was an alloy of copper and zinc and tin, in varying proportions. In fact, because the proportions and constituents of brass and/or bronze have varied so much over the ages, I've read that modern antiquarians and archaeologists prefer to lump them all together as "copper alloy" rather than try to split that hair.

(I'm not sure I'm into that. I mean, frankly I think going from the Stone Age to the Copper Alloy Age lacks a certain gravitas. Also, that would make the 1970s the Copper Alloy Age of Comics, which is a bit obnoxious. I mean, there was some good stuff in the Bronze Age. Also also, I wouldn't want to be the Copper Alloy Medalist in an Olympic event, that seems like kind of a snub to me. But anyway. :)

Regardless, gunmetal used to be used to make guns of all sorts, from artillery pieces down to handguns. The frames of early Colt and Remington revolvers were gunmetal, as were the receivers of 1860 Henry rifles (hence the "Yellow Boy" nickname). Only when smokeless powders, with their much steeper pressure curves, came along did it finally go out of fashion as a material for making the main parts of firearms out of, and even then it hung on as a decorative accent for a while (steel-framed Remingtons had "brass" trigger guards, for instance). In an application like this, where the device isn't meant to sustain high pressures, it still served perfectly well long into the smokeless era. Being mostly copper, it wasn't cheap, but it's durable and easy to machine, and it resists salt water corrosion better than steel, which made it attractive for a piece of equipment that would often be issued aboard ship.

One thing that's particularly surprising about the Mk IV, but that you can't see in the photos, is how heavy it is. My kitchen scale says it weighs 1 pound 12 ounces (that's 790 grams on the French scale)—about the same as an 1895 Nagant revolver. This is particularly striking when you consider that you can buy a brand new flare gun, roughly the same size, taking the same flares, that is made entirely out of plastic and weighs about an ounce. Of course, in 1918 there was very little plastic worthy of the name, and nothing that would have been suitable for something like this. Injection-molded polystyrene was a long way off. Even so, it seems a bit... overbuilt for its purpose. I suppose they wanted to make certain it was durable enough for field service; a flare gun won't do anyone any good if its barrel has gotten dented in all the excitement, after all.

Re the aforementioned, it's true that you can still buy standard 25mm flares that this gun will fire. One of the key things for which Very-style flare guns are still used is recreational boating. U.S. Coast Guard regulations stipulate that boats of a certain size operating in certain waters must have a certain number of flares aboard, and recommend that pretty much anybody doing any boating consider bringing along a few. You can also buy 25mm white parachute flares, good for illuminating dark areas outdoors, but those are longer than the barrel of the Mk IV and I don't know how well they would work out of it.

I haven't bought any (parachute or otherwise), because they're quite expensive—a pack of four 25mm red (the international distress color) aerial flares will run you $60-$80 plus shipping depending on which marine supply website you get them from—and besides which, what am I going to do with them? If I went out to one of the lakes nearby and fired one off, someone might think there was a boat in distress and try to come to the rescue. And if I did it not by one of the lakes nearby, I'd probably start a forest fire.

Still, it's a nifty thing to have. Maybe next year on Independence Day I'll give it a try, while it can blend into the general action overhead.

--G.