Originally posted August 22, 2017

This week's Gun of the Week is the one that prompted me to do the previous two, by way of background; and it's an old friend.

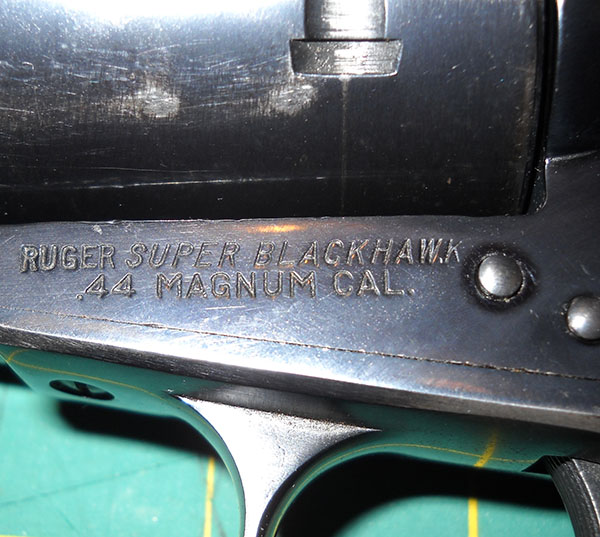

This is a Ruger Super Blackhawk, the large-frame .44 Magnum member of Sturm, Ruger and Company's long-running and popular Blackhawk single-action revolver family. And I'm almost ready to tell you more about it! Almost.

First, we need a little more background. In the early 1950s, the newly-formed Sturm, Ruger and Company was looking around for something to join Bill Ruger's new .22-caliber automatic pistol in its product line. Strange as it seems in today's saturated market, there was at the time a distinct demand for a reliable single-action revolver. Western films and TV shows were starting to become popular to a more or less culture-defining degree, and Colt had discontinued manufacture of the Single Action Army in 1941, so no one was servicing that market segment at exactly the time it was beginning to go big.

Recognizing the need, Ruger introduced a Single Action Army-derived revolver, the Single-Six, in 1953. The Single-Six chambered the same cartridge as Ruger's standard automatic, .22 Long Rifle (and thanks to the case head geometry and the fact that it didn't need to cycle a semiautomatic action, the shorter .22 Long and .22 Short cartridges would work in it as well), which made it easy and economical to shoot.

The Single-Six was an instant hit, to such an extent that it's never been out of production since, but it only addressed part of the need. We'll hear more about it, specifically, at a later time. For right now, what's important is that almost as soon as Ruger was satisfied that it was going to sell, he made plans to introduce a bigger model, sized for popular centerfire cartridges. This, which arrived on the market in 1955, was the Blackhawk, and it, too, was an immediate success that is still in production today.

The Blackhawk debuted in .357 Magnum, a longer and more powerful derivative of .38 Special dating from the 1930s. Although it looked and functioned very much like a Single Action Army, it wasn't a straight-up SAA clone. Most obviously from the outside, every Blackhawk has adjustable sights (which were optional on vintage Colts). On the inside, Ruger, ever the tinkerer, adjusted a few things about the mechanism; most notably, he abandoned the Colt design's leaf springs and replaced them with modern coil springs, which made the Blackhawk both more durable than the SAA, and easier to repair if the springs did break or wear out.

Just as the .357 Magnum Blackhawk was arriving in the marketplace, Ruger and his engineering team got wind of a new cartridge being jointly developed by Remington and Smith & Wesson, with the guidance of noted rancher, outdoorsman, shootist, hot-rod handloader, and serial Single Action Army exploder Elmer Keith, who is something of a patron saint to that band of the firearms community that likes to stuff as much gunpowder into a cartridge as it will hold and see what happens. Keith's creation was basically a stretched .44 Special, in much the same way that .357 Magnum was a stretched .38 Special, and logically enough was called .44 Magnum (more formally, .44 Remington Magnum).

An article on this hot new cartridge, and the revolver S&W were developing to chamber it, appeared in the March 1956 issue of American Rifleman (which at the time was a much more technical publication than it is today, on account of the 1950s National Rifle Association was an actual shooting sports organization, but that's a rant for another time). By that point, Ruger and company were already hard at work on their own .44 Magnum revolver. Legend has it they got a leg up when one of Ruger's engineers ran across some discarded .44 Magnum empties in a scrapyard. I'm not sure I believe that S&W's and/or Remington's people would have been that careless, but on the other hand, maybe so. People have screwed up bigger things than that.

At any rate, Ruger's .44 Magnum offering hit the market within months of Smith & Wesson's Model 29, and while the Model 29 would become more famous to the general public because of its starring role in the 1971 police drama Dirty Harry, the Super Blackhawk was the better-selling gun. It cost less and was easier to get hold of, particularly after Dirty Harry hit the cinemas and suddenly everybody wanted a Model 29. (It's also somewhat sturdier—not that the Model 29 is unsafe, by any means, but its lighter construction and the way Smith & Wesson double-actions work makes it more susceptible to wear with heavy use.)

Part of the reason why the Super Blackhawk was so quick to market was the fact that it is literally a slightly-beefed-up Blackhawk. The frame, which is the largest forging and the part that takes longest to make, is the same as the regular Blackhawk's; the design was already plenty strong enough to handle the demands of .44 Magnum (and indeed has been adapted to even bigger rounds since then). The two key modifications for the Super Blackhawk were an enlargement of the grip frame, to give the shooter more to get ahold of, and the use of an unfluted cylinder (except, for some odd reason, in the shortest-barrelled version). This makes the chambers a bit stronger, but its primary purpose is to make the gun heavier, which again is a recoil management strategy. For the same reason, the enlarged grip frame on the Super Blackhawk is steel, not aluminum as it is on the regular model.

The result, particularly with the old Single Action Army-standard 7½-inch barrel our example here sports, is a big, heavy, imposing handgun meant for a practical purpose: to make manageable use of what was, at the time of its introduction, the most powerful mass-produced handgun cartridge in the world. It's still quite a handful with full-power .44 Magnum loads, but fortunately for the casual shooter—as with other related families of rimmed cartridges—it works just fine with the earlier, less powerful cartridges .44 Magnum evolved from. It will happily use .44 Special rounds, or even that cartridge's still shorter predecessor, .44 Russian, if you can find any.

At the time of its introduction, besides a choice of barrel lengths (5½-inch, 7½-inch, or 10½-inch), there was one and only one option available on the Super Blackhawk: you could get it with a rib for mounting a telescope, or not. (Later on, it would also be offered in stainless steel as opposed to the traditional blued steel.)

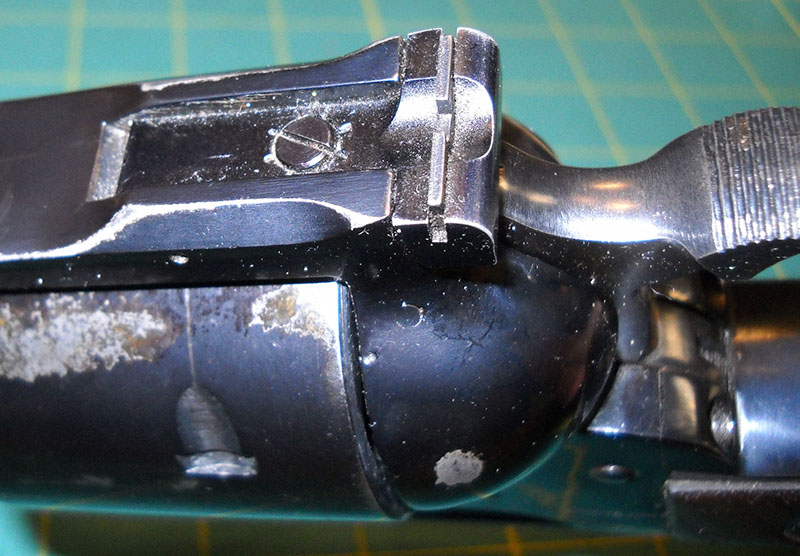

Although its inner working were modernized with the use of coil springs, the original models of all Ruger's single-action revolvers were just like their Colt ancestors in one important respect. Their lockwork, while coil-sprung, worked in the same way as the old Colts had. The old saying is that the act of cocking a Single Action Army spells out the name of the company ("C-O-L-T"), because it makes four distinct clicks: one for the "quarter-cock" position, one for half-cock, one from the cylinder being locked in place at its fully indexed position, and one for the sear engagement that readies the trigger to fire.

The original-model Rugers, like this vintage Super Blackhawk, work just the same. Their only concession to modernity in terms of their working parts was the inclusion of a spring-loaded firing pin in the frame, to be struck by the hammer and driven forward into the primer, so that the hammer has a smooth face instead of a protruding fixed firing pin.

With the cylinder dismounted, we can see that the firing pin protrudes when the hammer is down.

This means it's still not safe to carry an "old model" Single-Six, Blackhawk, or Super Blackhawk with the hammer down on a live round, just like it wasn't in the Single Action Army, or any of the percussion-fired revolvers that preceded it.

Ruger's engineers would eventually address this problem in the name of safety and reduced liability, in one of the few concrete examples I can think of offhand in which making a change for the laywers' sake actually improved the product. I'll show you what they did next time, when we talk about a gun that came after the changeover. This Super Blackhawk dates to before the change, which you can easily tell by looking at it from the three screws visible on the right side plate.

The "New Model" Blackhawk family sports two smooth pins in this location rather than the heads of three screws, making them easy to differentiate. This Super Blackhawk dates to 1969, so it's from before the introduction of the New Model—but well after the first significant change to the Blackhawk design, which was the addition of these "ears" on the top to protect the rear sight.

Pre-"ears" Blackhawks are called "flattops", echoing the common nickname of vintage special-order Single Action Armies with adjustable rear sights (which were also flat on top instead of sporting the long fixed rear sight trench of the standard version), and, since they were only made that way for the first few years, are prized on the collector market these days. This often happens with firearms that have had a visible design change during production, even when most such changes were meant as improvements. Collectors love making fine distinctions and tracking down variants, after all.

Another feature the Blackhawk family shares with the later-model Colt Single Action Army is its cylinder axis pin, which is retained with a little spring catch instead of the set screw that early SAAs had.

With the catch depressed, the pin slides forward easily until it's stopped by the finger tab on the ejector rod.

At that point, the cylinder can be taken out of the right side of the frame with ease; it just tips right out with the loading gate opened, and can be popped back in just as easily.

In the 60+ years they've been in production, a wide range of Blackhawk variants have been offered, many of which continue in production today. There's the "Bisley" version, which, like Bisley SAAs before them, have the modified grip configuration identified with that famous English shooting range. There are Convertible models, which use multiple cylinders to enable the use of incompatible cartridges with a common bore size (.45 Colt/.45 ACP and .357 Magnum/9mm Parabellum are the ones that come to mind). There's even one that takes the .30 Carbine cartridge, which is unusual in a handgun. They can be had in blued or stainless steel, with wooden or hard rubber grips, and from customizers in pretty much any configuration and finish the purchaser can think of.

The company still bills the Blackhawk as "the most advanced single-action revolver ever made," which is probably true. Apart from showy tweaks like the Cimarron Thunderer mash-up, I can't think of anyone else who is actively developing single-action technology these days. I like to think that if any of the big names of the Old West got hold of a new-today Blackhawk, he would find operating it completely intuitive (once he figured out the newfangled gate mechanism—again, more on this next time), but he'd be blown away (er, as it were) by the manufacturing, if he had an eye for that kind of thing.

The irony there, at least to me, is that this same development makes the Blackhawk "too modern" for the more hardcore cowboy shooters today. The Ruger company recognizes this, which is why they also offer a model called the Vaquero specifically for those folks. Where the Blackhawk is a modernized and improved Single Action Army, the Vaquero is a closer-to-exact SAA clone in terms of its shape and features. It has fixed sights and the ejector rod is more like the ones on the old Colts—but it still has the New Model operating system, because Ruger is committed to that particular improvement to a degree that frankly seems faintly weird to an outsider. At least this outsider.

Anyway, here's a little more about this individual Super Blackhawk. My grandfather bought this gun new in 1969, four years before I was born, and for one specific purpose, which he was still using it for 20 years later. Contrary to the image projected by Ruger's marketing, this purpose was not big-game hunting, but it did have to do with large animals.

See, in those days Gramp supplemented his income with a spot of fur trapping in the appropriate seasons, which meant he spent a fair bit of time tramping about in the woods around Oxbow, tending his trap line. Now you might not think this is the sort of duty that calls for a .44 Magnum pistol, and in itself, it isn't. Any direct need for a firearm in that task would call for something much smaller, and that is in fact exactly the purpose he carried his Hawes Favorite for.

The Super Blackhawk, on the other hand, went along in case he happened to have an argument with something larger and more ill-tempered than a muskrat. He never had to use it, but he put a lot of mileage on it in the course of his trapping career, all the same. In the off-season, he used it for target practice and training. It's the first centerfire handgun I ever shot, loaded with much milder .44 Special rounds. The same is probably also true of my two younger cousins, who also learned to shoot from our grandfather.

I had this gun in my possession for a few years after high school, but gave it back when I moved to California; later, when Gramp started paring down his collection in anticipation of his and my grandmother's eventual move into assisted living, he hung onto the Super Blackhawk until last.

Unfortunately—and for no reason I can readily identify—those last few years in its holster in a drawer took a toll on the pistol's finish that all those years of being actively carried on the trail hadn't done. When I knew it in the '80s and '90s, it had the usual sort of edge whiting and general wear that a well-used gun can be expected to have, but when it came back here a couple of years ago, I discovered to my dismay that this had happened.

All that bluing that's missing from the side of the barrel and cylinder is on the inside of the holster. So I know in general terms how it happened, that much is obvious, but I'm completely at a loss as to why it happened over the course of a few years in a drawer, when decades of being carried regularly in the field, in the same holster, didn't.

It's a shame, and it leaves me with a bit of a quandary. Refinishing firearms is a thing that a lot of people Have Opinions about in the collecting world. Back when I used to read magazines like Guns & Ammo, they all had a "what is this gun I found and what is it worth?" letter column, and practically every letter in them was the same:

Dear Dr. Whatgun,

I found this old pistol in my late Uncle Frank's sock drawer when we were clearing out his things after the funeral (see attached photo). Aunt Ethel thinks it must be the gun he told her he traded some blue jeans to an East German for when he was overseas in the Army. The only marking on it is this weird fishhook thing. What is it and is it worth anything? Dave in Seattle.

Dear Dave,

Wow! That is a ZAP-52 pistol, which was made by Zkrznyy Arsznyly ("state arsenal") Przkvszno in Transbelvia sometime between 1952 and 1967. They were the issue sidearm for the Transbelvian People's State Defense and Anti-Imperialist Aggression Forces until 1995. That's a very rare find, it's thought that there are no more than five or six of them in the United States. Ordinarily it would be worth at least $4 million, but unfortunately it looks like your uncle's has been reblued, so it's only worth about 75¢. Still, it's a really interesting find, congratulations! Yours, Dr. Whatgun

I'm not terribly bothered about the Super Blackhawk's collector value, but all the same, that kind of thing gives me pause. On the other hand, if I leave it with those big bare patches, it'll rust, and that won't do. I'll probably have to bite the bullet (as it were) and have it professionally refinished one day soon. (I will certainly not take a fine old family heirloom like this and try to touch it up myself with cold bluing compound. That would be like that old lady who tried to fix the painting of Christ.)

Ordinarily, in a situation like this, and knowing Ruger's long-standing practice of supporting their back catalog (you can still get an owner's manual for this revolver, or the original retroactively-Mark-I .22 pistol, or anything else they've ever sold, by writing to the company), I would inquire of them directly as to whether they could quote me a price for refinishing this revolver. Unfortunately, that's where I run up against another of their renowned company commitments, namely to the enhanced safety of the "New Model" single-action system.

You see, they offer a free upgrade for any Old Model Blackhawk, Super Blackhawk, or Single-Six an owner cares to send in, no matter how old it is—but they refuse to do anything else to an Old Model single-action without performing said upgrade first. If you send them an Old Model revolver for anything at all—replacement of a broken spring, repairs for a damaged sight, anything—they will do the New Model overhaul to the lockwork before they look at anything else.

Which is a problem, because I don't particularly want the New Model overhaul on this Super Blackhawk. I know it's not safe to carry with the hammer down on a loaded chamber, and that's absolutely fine, because I'm never going to do that. I don't object to the New Model design at all, nor do I have a problem with Ruger offering a free upgrade to anyone who wants it. I am a little miffed at the high-handedness of that last part, though. It seems a bit disproportionate for the level of the problem. The shortcomings of the traditional SAA-style action aren't a hazard on the same level as, for instance, the habit pre-FS Beretta 92Fs had of occasionally flying apart.

So, that rules out sending the Super Blackhawk back to Ruger to have its finish problems looked after. Instead, I'll have to shop around a bit.

In the meantime, it's safe in a drawer with some others of similar types, no longer being kept in its holster, so at least the problem won't get any worse while I look into remedies.

--G.