Originally posted April 23, 2018

In 1915, France had a problem. I mean besides Germany, although it's what you might call a secondary effect of the French's larger overall problem with Germany, to wit: not enough guns to shoot all the Huns. France had its own arms factories, of course, but as the war ramped up in the fall and winter of 1914-15 and it became obvious that it wasn't going to be over by Christmas after all, French ordnance authorities decided to put all the native production capacity into the weapons that were larger and considered more strategically important: rifles, machine guns, that sort of thing.

That left a lot of French soldiers and especially officers in need of handguns, which were considered important enough that everyone ought to have one, but not important enough to devote capacity at the state arsenals such as Ste-Etienne or Châtellerault to their production. The obvious outside source for such things, all other factors being equal, would have been Liège in neighboring Belgium, which was one of the great handgun manufacturing centers of the world, but, well, the Belgians had their own problems, seeing as how the German Schlieffen Plan specifically called for basically their whole dang army to crash through Belgium on the way to invading France.

(This, by the way, was the technical reason why the British even got involved: they were bound by treaty to defend Belgium, in exchange for the latter country's neutrality in the complicated web of pre-War European relations.)

Fortunately, France has another convenient neighbor, and at the time, that neighboring country contained a region renowned in the firearms community for two things: a thriving artisan firearms manufacturing scene, and a deeply cavalier attitude toward intellectual property.

Eibar is a town in the Basque country of northern Spain, conveniently located quite near the French border, and in the decades immediately preceding the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), it was the hub of the country's firearms industry. Firearms manufacturing in Eibar didn't quite work like it did in places like Châtellerault, or Liège, or (for instance) Oberndorf am Neckar in Germany, though. Those were cities that had either government arsenals or large, massively organized corporate arms factories. In Eibar, what they had was a great multitude of small, usually family-owned machine shops populated by skilled craftsmen who could turn out pretty much any metal objects you wanted—bicycles, bayonets, pistols, whatever.

(When I'm speaking of Eibar here, I'm really referring to what a modern chamber of commerce would probably call the Greater Eibar Area. Nearby towns like Guernica, which would become famous as the subject of Pablo Picasso's Civil War painting of the same name, were also prominent in the local artisan firearms scene. That's one of the reasons the Nazi Condor Legion bombed it on Franco's behalf. But I digress.)

Now, it could have been (and was) argued that one thing Eibar didn't have was any really first-rate firearms designers, the likes of J.M. Browning (who did a lot of work in Liège before and after the war) or the Federle brothers at Mauser. And, to be fair, that was probably true. The bigger firms in Eibar, at least, did have some engineers, they weren't all simply machinists, but none whose names would be indelibly linked to the design of a famous locally originating product like Browning's FN 1903 or Georg Luger's DWM Parabellum pistol. The works of the Eibar shops, rather, were largely—often blatantly—imitative.

The reason this was so is because the Spanish Republic of the time had a curious quirk in its patent law. See, contrary to popular supposition, there is really no such thing as an international patent. Nowadays, since 1970, there is the International Patent Cooperation Union, under the auspices of which the signatories of the Patent Cooperation Treaty coordinate their application procedures, and that gives something of the illusion of an international patent, but in reality, individual patents must still be sought in all the signatory nations. The PCT isn't the patent equivalent of what the Berne Convention does for copyrights; there isn't any such thing.

Before 1970, there wasn't even that level of coordination. An inventor or corporation who wanted to patent something in more than one country had to apply separately in each one. An American company would probably start with the U.S. patent, but if it did not also seek patent protection for its invention separately under the laws of, say, the United Kingdom, said invention would not be protected there; anyone in the UK who got hold of the American patent document (which must, by law, contain a detailed explanation of how to make the thing being patented, and which, with a few specialized exceptions, are public records available to anyone who wants them) could then make and sell as many of the thing as they dang well pleased, with impunity.

With me so far? OK. Here's the Spanish quirk: You could only patent something in Spain if you made it in Spain. If you were an American, say, and you had a hot idea for a new kind of automobile axle or whatever, the Spanish government would happily extend you the benefit of a patent, providing a protected monopoly on its production and sale in Spain for however long their standard patent term was... but you would have to build a factory in Spain and make the axle there in order to enjoy said benefit. If you didn't, the Spanish government took that as evidence that you didn't care that much about it.

This is not how it worked in most western countries at the time. If an American company patented an invention in Britain, even if it didn't set up a British subsidiary to make that invention in the UK, British law would still prevent some local entrepreneur from setting up shop without license and knocking the things off. Not Spain. If you weren't going to build the thing in Spain, then they'd be just as happy to let someone else do it and not pay you a cent. Or peseta. Or whatever.

This little bit of legal obduracy gave the craft manufacturing firms of Eibar a great advantage. They could avail themselves of all the finest, freshest, most cutting-edge firearms technologies available on the open market without employing the people who designed them or paying royalties to said people. All they had to do was write to the patent office in Brussels or Washington or wherever and get detailed specifications on how it's all done.

In 1915, this was great for the French, because it meant they could contract with pretty much every machine shop and factory in Eibar to build them compact, reliable automatic pistols based—completely illegitimately, and so very, very cheaply, but totally legally!—on one of the most popular and well-regarded designs of the time, the Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless.

That pistol was known by many names depending on who made it, but is most popularly called the "Ruby", and the factories of Eibar cranked out literally a million of them for French orders during the war. However, the gun we're here to talk about today is not the Ruby...

... it's this.

Some of you are probably looking at that photo and thinking, Uh, OK, it's a Smith & Wesson K-frame. The K-frame, also known as the Military & Police Model and (since 1957) the Model 10, is one of the twentieth century's ubiquitous midsized handguns. It originated as the Hand Ejector Model of 1899 (guess when!) and, in incrementally modernized but externally identical forms known by a number of different names, went on to be the basis of the revolvers carried by more or less every American uniformed cop between about 1920 and when they started buying Glocks in the 1980s.¹ During World War II, more than half a million M&Ps chambered for the British .38/200 cartridge were provided through Lend-Lease to the Allies under the name "Victory Model". As the Model 10, it's still in production today. Literally millions of these things have been produced by S&W since the base model debuted in 1899...

... and this isn't one of them. Notice the complete absence of Smith & Wesson markings on either side.

If there's one thing the venerable firm of Smith & Wesson, headquartered in lovely Springfield, Massachusetts, has never, ever been bashful about, it's putting their name on the product. Well, it's nowhere to be found here. In fact, this gun has no markings of any kind on its sides. No brand name, no place of manufacture, no caliber, no proof or inspection stamps, no military acceptance marks... nothin'.

Nevertheless, we can tell from one of the very few markings that are on the gun, in less obvious places, that it, like the million or so Ruby pistols, was manufactured for the French military during World War I. In addition to the automatics, the French bought a fair number of S&W M&P Model of 1905 clones from the machine shops of Eibar, and this is one of them. Like the Rubies, they came from all sorts of different vendors, each of which took a slightly different approach to cloning the Model 1905. This particular one was manufactured by the firm of Trocaola, Aranzabal y Compañía ("and Company").

We know that because the only markings on the whole gun are two copies of the serial number (one on the front of the cylinder crane, one on the butt of the grip frame), three instances of one tiny mark we'll get to in a minute, and, up on top of the barrel, this.

(It's in pretty small type and hard to see, so I've zoomed in pretty tight for this shot; in practice the whole line of lettering is only a couple of inches long.)

Parsing out the terrible kerning, that says "TROCAOLA ARAMZABAL Y CIA • EIBAR (ESPANA)". There are two things about this that are... interesting. One is that evidently the manufacturers did not spring for the non-freeware version of their stamping font; it should be CÍA (short for "compañía", of course) and ESPAÑA.

The other is that the company's name was Trocaola, Aranzabal & Company.

Yup. That's right. They spelled their own name wrong in the only lettered stamping on the gun.

That may not tend to inspire a great deal of confidence in the skill of Señores Trocaola, Aranzabal, et al., but that mildly embarrassing gaffe notwithstanding, this is a pretty well-made gun. I've handled some pretty low-end revolvers in my time, guns of the type that would later be tagged with the cautionary nickname "Saturday Night Special"—the kind that are so cheap and flimsy that you can tell just from handling them they'd be as much of a danger to you as to anyone you might happen to menace with them.

This is not one of those guns. The quality of the tool work is good, the finish is very good given the age of the gun (admittedly, it might have been refinished at some point, but it does show a bit of pitting on one side, and anyway, who would bother?), nothing is loose or wobbly or feels like it's going to fall off. The cylinder locks up solidly and seems to be nicely in time. It's a decently made early-20th-century double-action revolver. If you didn't look closely, you wouldn't automatically assume it wasn't a Smith & Wesson, which is reasonably high praise in this context.

Mechanically, it's not the most revolutionary piece (although it would have been pretty high-tech for its time): a solid-frame, single/double-action revolver with a six-shot swing-out cylinder, opening to the left and operated by a distinctively S&W-style thumb latch.

On the inside, it's interesting in that it's not quite a straight-up copy of a "third change" M&P Model 1905 (the version that would have been current when the clones were made). The lockwork has been modified, simplified, and arguably improved a bit, presumably to make it easier and cheaper to manufacture with the equipment to be had in Eibar in 1915. I'm not going to pull the side plate off mine and get into that, partly because I don't have a "real" Model 1905 to compare it to anyway, but mostly because C&Rsenal did a Primer episode on these last year and Othais will happily take you through the changes much better than I could do it anyway.

It's interesting to me that the French didn't put any markings of their own on these, despite the fact that they were purchased through military contracts for direct issue. They just hauled them out of the crates they arrived in, maybe tested a few, and then handed them straight out to whoever they figured ought to have them. No acceptance stamps, no PROPRIÉTÉ DE LA FRANCE, nothing at all to indicate they weren't just bought off the counter at some hardware store in northern Spain (or wherever such things were sold to the General Public in that area in those days).

Well... almost nothing. The lanyard ring on the butt of the grip strongly hints that this gun was made with military use in mind, since at that time virtually no self-respecting military pistol was without one, and civilian handguns generally didn't have them. More conclusively, though, remember the "three instances of one tiny mark" I mentioned earlier? Although tiny, and affixed to the gun in inconspicuous places, and absolutely meaningless to anyone who doesn't know the code, they are positive proof that this gun was made for the French during the war, and they fill in an important piece of missing information: what cartridge this revolver is chambered for.

This goes back to the reason why the French bought bunches of these guns in addition to the million-plus Ruby automatics they were already buying, to wit: they had a lot of ammunition to use up that wouldn't go in the Rubies. Like the Colt 1903 they were riffing on, Ruby pistols were (almost always) chambered for 7.65mm Browning Short, also known as .32 ACP. That was plentiful enough that the French didn't have any trouble getting hold of it in bulk and issuing it to anyone who got a Ruby, but it wasn't their standard handgun cartridge, of which they still had a great deal in stock.

No, on paper the official French standard handgun cartridge of World War I was still the 8mm French Ordnance cartridge, as employed by the Revolver d'Ordonnance Mle. 1892—the gun which was still the French Army's official sidearm, but which the French arsenal system could no longer spare the capacity to produce. And that's the cartridge that these revolvers were made to use, rather than .32 ACP (which is a semi-rimless cartridge and would be kind of a pain to put in a revolver), or any of S&W's own .32 or .38-caliber cartridges (as the "real" Model 1905s would take).

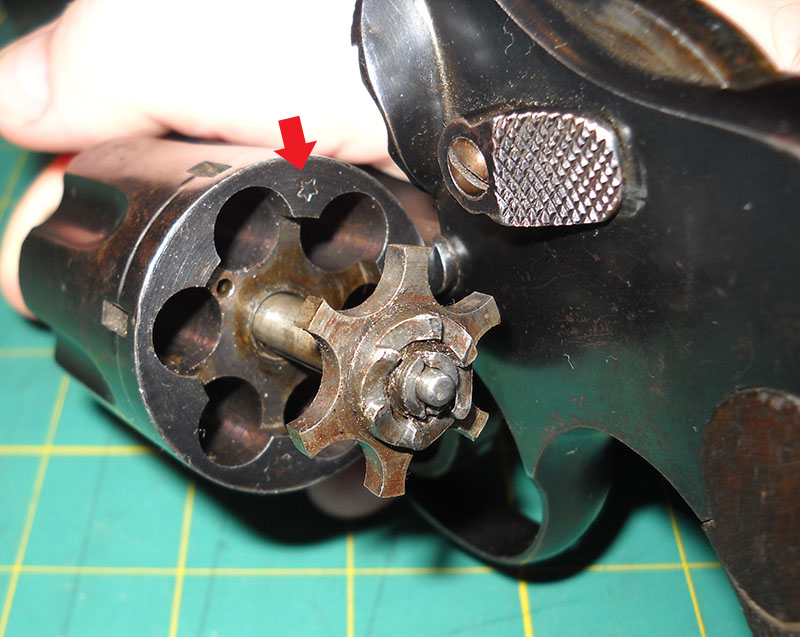

And we can tell that because of this tiny marking right here.

See that little star stamped on the back face of the cylinder, indicated by the red arrow?² According to Othais in the video above, that indicates that this revolver is chambered for 8mm French Ordnance. Now, that would only be true if this revolver had been made for the French war effort; no one other than a French soldier was going to have any use whatever for a revolver chambering that cartridge in 1915.

I love unraveling little mysteries like that. The shop I bought this gun from had no idea what it was. Whoever had written up the tag for it presumably didn't know the (admittedly obscure) history of these guns, and when they looked at that top engraving, they could only parse it as the kind of gibberish one often finds on Mystery Pistols.³ They also took a wild stab at the cartridge, probably by miking one of the chambers. The end result was that it was tagged something to the effect of "CHINESE?? S&W VICTORY COPY - .32 S&W???"

To be fair, I wasn't entirely sure what the heck it was either, but given what they were asking for it, I figured it would be worth the investment to pick it up and do some research. Then I never quite got around to it, and then Othais did it for me, so that worked out just fine. :)

For the record, though I am confident in the quality of this pistol's manufacture, I've never actually shot it, for the simple reason that 8mm Ordnance ammunition is pretty much impossible to find and stupid-expensive when you do. One of these years, if I ever get my reloading stuff set up, I might dig out my Manual of Cartridge Conversions and see if there's anything out there a person might make some out of. For now, it stays in the drawer with the old Mle. 1892, presumably reminiscing about how they gave the Boche what for.

¹ The equally ubiquitous .38 (S&W) Special cartridge was originally developed for this model, and specifically to edge out the .38 Long Colt in performance—perhaps S&W's revenge for Colt's rebranding of the original .38 S&W as ".38 Colt New Police" for sale in its previous generation of competing revolvers.

² There are actually two of them, directly opposite each other, and a third hidden away on the front of the trigger guard; the indicated one's the only one that really shows up in this photo, anyway, and the one on the front is obviously completely out of shot.

³ Mystery Pistols are weird and wondrous (alleged-)firearms made, usually by hand, by backcountry craftspersons, usually in the Third World. They are often made with apparent visual, but not mechanical, reference to existing firearms, and feature bizarrely cargo-cultish imitations of features, made by people who knew what they looked like on real guns but evidently had no idea what they were supposed to do: Adjustable-looking rear sights that can't actually be adjusted and are marked with meaningless, arbitrary numbers (often without even an actual notch in them); little levers that look like safeties or slide stops but don't really do anything at all; things that look like Mauser C96-style hammers but are really just shapes machined into the back of the slide; and so on. Since most of them were made by people who couldn't read the markings on the proper guns they were using as reference, and who expected that their customers wouldn't be able to either, they often have hilariously nonsensical stampings on them, such as faux Mauser, FN, or Walther logos (sometimes all three on the same gun), and meaningless repetitions of common words like BROWNINGS and BREVETÉ (French for "patented").

Ian over at Forgotten Weapons has something of a fondness for Mystery Pistols, which I confess I've rather caught from him. In fact, he's got a whole playlist of videos about weird and wacky mysteries and knockoffs, for however much longer YouTube keeps allowing such content to exist.