Originally posted March 25, 2020

Way, way back in our Winchester Model 94 episode, we heard the names of Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson. In 1852, they teamed up and founded the Smith & Wesson Company, for the purpose of further developing the Volition repeating rifle and "rocket ball" ammunition concept, which Walter Hunt had invented in 1848, and Smith and Lewis Jennings had improved on the following year. By 1855, the company had been reorganized as the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company (after the name chosen for the improved Volition rifle); shortly thereafter it was taken over by one of the investors, Oliver Winchester, and would eventually metamorphose into the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, of lever-action rifle fame.

Smith had left the company at the time of Winchester's takeover, while Wesson stayed on for a few months as Volcanic's plant manager. While all this was going on, Wesson noticed that Samuel Colt's patent on the self-indexing revolver was soon to elapse. He began tinkering around with a revolver design of his own, to use the newfangled metallic cartridges (something Colt had not yet done), and in the process of researching its patentability he discovered Rollin White's patent covering the concept of a revolver cylinder with its chambers bored straight through.

Wesson was going to need to do that to make his metallic cartridge idea work, so in 1856, he left Volcanic and teamed up with Horace Smith again. They founded their second joint venture, the Smith & Wesson Revolver Company, and approached White to acquire an exclusive license to his patent.

Here, as we have seen before, Smith and Wesson were very canny and Rollin White was very not, because the former did not make the latter a partner in their company. Instead, they came up with a licensing agreement whereby they would pay White a flat royalty for each revolver produced using his patent (25¢, pretty generous money for the time), and—critically—White would be the one responsible for defending the patent in court. Either White didn't anticipate the absolute flood of imitators he was going to have to sue, or he just wasn't very good at math, because the costs of all those lawsuits bankrupted him while Smith and Wesson, as the company principals, walked away with colossal profits.

At any rate, that was all in the future in 1857, when the Smith & Wesson Model 1 revolver entered production. By modern standards this was a tiny and virtually powerless handgun, chambered for the .22 Short rimfire cartridge—which is an utter pipsqueak today, and would have been even more so in the 1850s, decades before the invention of modern smokeless powder. I would speculate that only the fact that antibiotics hadn't been invented either made weapons like the S&W Model 1 at all fearsome.

This didn't stop the Model 1 from being hugely popular, particularly after the Civil War broke out in 1861. While it was never adopted as an issue firearm by any military I know of, S&W sold so many of them as private sales to soldiers wanting a sidearm that demand outpaced capacity, spurring the company to expand. At the same time, Wesson developed the Model No. 2 Army, which debuted that same year and was essentially a scaled-up Model 1 for the somewhat less anemic .32 rimfire cartridge. In 1865, there followed an "intermediate" version, a Model 1-sized .32 cleverly named the Model 1½.

The Models 1, No. 2 Army, and 1½ (in the first two of its three versions) were all "tip-up" revolvers, meaning that they were reloaded by breaking the frame open, but the hinge was at the top rather than the bottom. This was fine for the wimpy rimfire cartridges they chambered, but after the war, when demand shifted from emergency backup handguns for soldiers to heavier hardware for people heading West, S&W needed to come up with something bigger and stronger. This, introduced in 1870, was the Model 3, a beefy .44-caliber revolver that broke at the top.

The Model 3 became fairly famous in its day as the adopted sidearm of both the United States (1870) and Imperial Russian (1871) armies, as well as the basis for the "Schofield" version that was issued to the U.S. Cavalry. In S&W's commercial lineup, it was followed in 1876 by the confusingly named Model 2, which was a scaled-down .38-caliber version of the Model 3 and nothing to do with the earlier Model No. 2 Army.

All of Smith & Wesson's revolvers had single-action lockwork until 1880, when the company introduced a double-action version of the Model 2 (presumably to compete with Colt's Model 1877). This was available in .32 and .38 calibers, and was reasonably popular; the .38 version was adopted as a police weapon in several cities, and both sold well on the commercial market.

By the late 1880s, though, Daniel Wesson had come up with a new idea, one based on the double-action Model 2, but with new features that better suited it to the "pocket gun" market. This debuted in 1887 (for the .38; 1888 for the .32 version) under the name "New Departure", referring to the change in design direction it represented for the company's products, but became better known as the Smith & Wesson Safety Hammerless. Which, at last, brings us to our actual Gun of the Week.

Behold, a .32-caliber Safety Hammerless. This one is a Third Model, manufactured circa 1930.

One thing that photo doesn't really capture, even with the crafting mat scale markings in the background, is how small this revolver really is. For that, you must see it in a more intuitive context.

Now I'll be the first to admit that I don't have small, delicate hands, but even so, this pistol is tiny. The .32 version of the Safety Hammerless is based on the frame size of the Model 1½, which was not much bigger than the minuscule original Model 1, but without a hand for reference, it only really shows in the strange-looking proportions of the trigger and trigger guard.

Note the cartridge marking:

At the time this revolver was designed, .32 S&W was the only .32-caliber centerfire cartridge used in S&W revolvers. In 1896, when the swing-out-cylinder Hand Ejector model was introduced, it brought with it a lengthened version called .32 S&W Long, which retroactively made the original .32 S&W Short, but it appears they didn't bother altering the stamp for the .32 Safety Hammerless's barrel accordingly; this one was made around 1930 and it doesn't specify "Short". I haven't tried it, but given the stubbiness of the cylinder, I assume .32 S&W Long wouldn't physically fit in this gun, and so perhaps they deemed it not worth changing the stamp.

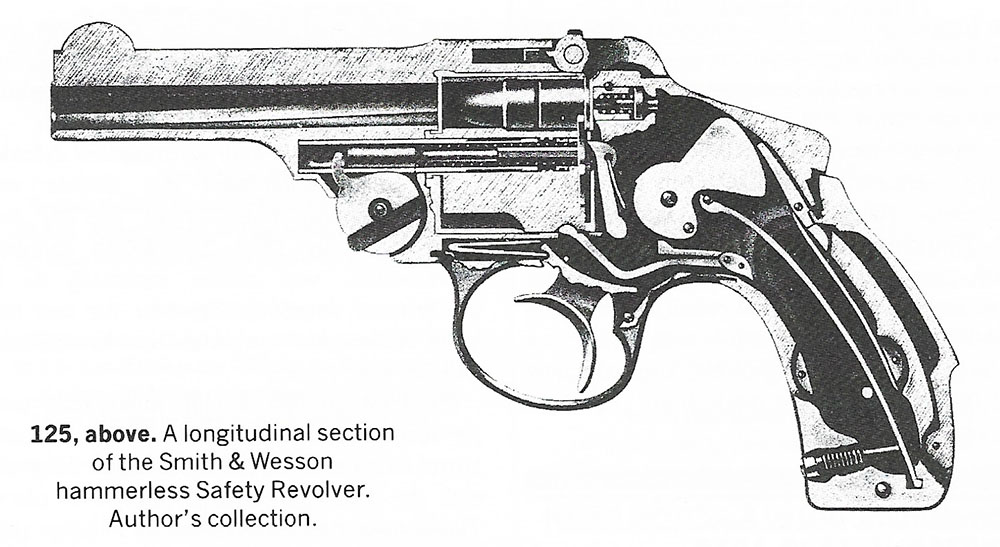

At any rate, you can probably guess how it got the "Hammerless" part of its name, although, like other guns we've seen with that moniker, it isn't technically true. The Safety Hammerless does have a hammer, it's just completely enclosed within that "hump" at the back of the frame. You can see that in this handy sectional diagram, which is from George Markham's Guns of the Old West¹.

This not only reveals the Safety Hammerless's hidden hammer, but also shows the simultaneous ejector built into the cylinder axis, which works just as it does on the later Webley break-top revolvers, the spring-loaded, rebounding firing pin, and the double-action trigger mechanism. A bit strangely, the revolver is depicted in this diagram in a state it can never actully be in for more than a split-second at a time, with the firing system cocked. Since the hammer is fully enclosed, the revolver is double-action-only, so it can never be cocked and left that way.

Also visible in the diagram is the other part of the Safety Hammerless's name, which is that—unusually for a revolver—it has a grip safety. That lever at the back of the grip must be depressed in order for the trigger to work, and the only practical way to do that is to hold the grip quite firmly. Between that and the double-action-only trigger, this revolver has a surprisingly heavy trigger pull for its size.

This was deliberate on Wesson's part, and plays into the other side of the double meaning "Safety" has in the product's name. Not only does it have a safety (the mechanism), it was designed with safety (the general concept) foremost in mind. The shrouded hammer and small size suit it for pocket carry, and Wesson wanted to make absolutely sure that it was the safest pocket gun he could devise. Customers shooting themselves, after all, is bad for business. Hence the rebounding firing pin, which makes it safe to carry with all six chambers loaded, and the combination of the hidden hammer, grip safety, and heavy trigger pull, which make it virtually impossible to fire by accident—say, while pulling it hurriedly out of a coat pocket prior to putting it to use.

The unusual configuration of the grip safety lever gave the New Departure/Safety Hammerless its third name, never official, but widely adopted. To this day, revolvers of this type are commonly known as S&W "lemon squeezers".

Over on the left side, the only markings are the repeated Smith & Wesson logo on the hard rubber grip and the company's name on the side of the barrel. Note the cover plate, which allows access to the lockwork should repairs be needed. I decided not to remove that, since the drawing from Markham's book shows what's under it in enough detail for anyone.

Opening the frame is accomplished by pinching and pulling up on the little knurled pads at the top rear, which unlocks the latch and allows the revolver to be swung open. The latch is a simple shroud and tongue that interact with two lugs on the top of the grip frame:

As in a Webley, pivoting the cylinder/barrel assembly open automatically actuates the ejector, pushing the empties out of the cylinder. (Note how, in this photo, the Canon's flash has done its usual job of making the side plate look much rustier than it is in real life.)

Snap it open firmly enough (but not too hard), and the ejector will pop the empties clean out of the gun. Otherwise, just turn it over and give it a shake, and they should fall out. Once it reaches its full extension, the ejector pops past a pawl and the spring pulls it back down into the cylinder, ready to be reloaded. The barrel can be opened past 90°, making the cylinder very easy to access for reloading.

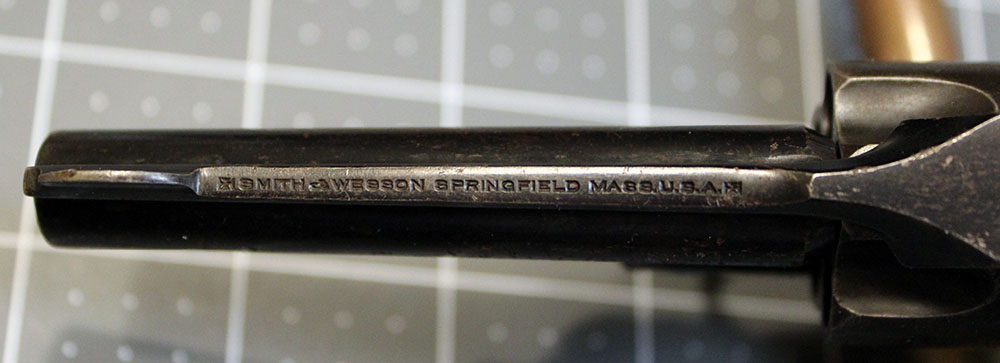

Up on the top rib of the barrel is another stamp, this one simply notifying the reader, if he or she didn't already know, that Smith & Wesson is headquartered in Springfield, Massachusetts.

I originally took this shot to get a better look at the underside of the frame latch, but then noticed that the gun's serial number is also repeated on the cylinder face. No proof marks, since this gun was not exported and proofing isn't as obsessively recorded in the US as it is in most of the rest of the world.

The Safety Hammerless was a popular gun despite the limitations of its ammunition (which were not considered as important in its day than they would be today)—popular enough that they remained in production long after their successors, the swing-out-cylinder Hand Ejector models, came along circa the turn of the 20th century. They weren't discontinued until 1940, with production ending in 1941; by then the American arms industry was gearing up for World War II (even though the country's own armed forces wouldn't be involved until nearly the end of the year), and larger, stronger, more powerful weapons were in greater demand.

The top-breaks would never return to production after the war, although the Safety Hammerless fully-shrouded hammer, double-action-only concept returned in the 1952 J-frame Centennial model, which eventually became the Model 40 and spawned variations that continue in production to this day.²

¹ Markham, George. Guns of the Wild West: Firearms of the American Frontier 1849-1917 (London: Arms & Armour Press, 1991), 72.

² The Centennial and its descendants are not to be confused with the Bodyguard, which is also a J-frame S&W revolver with a shrouded hammer, but leaves a slot to expose the thumb pad so that the gun can be worked in single action.