Originally posted March 13, 2020

This week in Gun of the Week, let's take a look at something that's also from 1935 (sort of), but a bit more French.

At the end of the Great War, the assortment of French military small arms was, with the best will in the world, a hot mess. Over the course of the continuous four-year emergency that was the war in France, virtually anything and everything that could send a piece of metal downrange was pressed into service in one capacity or another. Obsolescent rifles and handguns, developmental items not ready for prime time, messy but expedient emergency inventions, it all got thrown into the lines without much regard to long- or even medium-term viability. If a man could theoretically shoot a Boche with it, someone ended up having to carry it.

It was all such a mess that, at war's end, the French government unilaterally declared everything then in inventory obsolete. With the Germans defeated (sort of) and the world at peace (nominally and for now), they were going to chuck everything into warehouses—even under the circumstances, they weren't about to throw anything away that might be useful in the next emergency—and start over.

The handgun situation was particularly chaotic. At the start of the war, the standard-issue officers' sidearm of the French Army was still the Revolver d'Ordonnance Modéle 1892, but there weren't enough of them to go around. As we saw in the Franco-Spanish Revolver Mystery, the French dealt with this by buying loads of pistols in from the gunsmiths and machine shops of Basque Spain, including a literal million .32-caliber Browning knockoffs that went under the collective name of "Ruby".

The problems with this from a postwar standpoint were many, but the two biggest ones were consistency and ammunition supply. Consistency because the Spanish guns came from a multitude of manufacturers, some more competent than others, and so ranged in quality from "quite good" to "junk" to "actively dangerous to the operator". They also tended to have similar controls, because most of them were copies of the same original gun, but not always and not exactly, which made training soldiers in their use a challenge. Ammunition supply because although most of them were chambered for .32 ACP (or 7.65mm Browning Short, as the French would have known it), the voracious procurement machine had swept up pretty much anything on offer, including .380s and, as we saw before, piles of revolvers for the old 8mm Ordonnance cartridge. This made the prospect of supplying troops armed with this jumble sale of an inventory a real hairball.

In response, the French government issued a call for trials to select a totally new handgun upon which to standardize its armed forces. In its original form, this call specified that the candidate pistols should be semi-automatic, chambered for a 9mm cartridge (which one, specifically, seems not to have been noted, but they probably wanted 9mm Parabellum, since they'd been so impressed with the German guns using that cartridge during the war), have a barrel 100 millimeters (about four inches) long, and be capable of holding seven cartridges.

In the early twenties, various designers got to work on candidates for the French pistol trials, including no less a personage than John M. Browning (1855-1926) himself. Browning offered a couple of different prototypes, including a handgun with a straight blowback action (always a dicey proposition in 9mm Parabellum) and one with a locking breech. Along the way, he also included an invention of his protégé at Belgium's Fabrique Nationale, Dieudonné Saive (1888-1970), providing a locked-breech prototype fitted with a then-unprecedented 15-round magazine.

(I have seen it claimed that Browning himself didn't hold with the high-capacity pistol magazine idea, and that Saive had to build one just to prove to him that it would work, but if that's so, he was apparently on board enough with the idea after that point to submit it to the French trials.)

Toward the middle of the 1920s, another corner of the French ordnance establishment was working on submachine gun designs, all parties concerned having seen how frightfully effective the German MP 18/I had been in the hands of the late-war Sturmtruppen. For reasons I was not able to find much information about, the cartridge they ended up standardizing on for their SMG project was .30 Pedersen. This is a bit odd, since .30 Pedersen was designed for one very particular use, to which it was then never put.

As its name suggests, .30 Pedersen was the invention of famed hard-luck firearms designer John Pedersen (1881-1951). He developed it specifically for use in the eponymous Pedersen device, which was—I kid you not—a blowback semi-automatic action designed to be a drop-in replacement for an M1903 Springfield rifle's bolt. This was to be the United States Army's wonder weapon in the great Spring 1919 offensive on the Western Front, a device which enabled each rifleman on the line to convert his high-powered bolt-action rifle into a pistol-caliber automatic rifle and storm the German lines in a hail of little bullets. In the event, the shooting stopped in November 1918, there was no Spring 1919 offensive, the Pedersen device was never issued, and most of them were scrapped.

The cartridge developed to be used in the Pedersen device, which used the same bullet diameter as .30-'06 Springfield (so it could be shot through an M1903's bore without modification), had no other use and probably should have disappeared along with it, but for some reason the French decided it had potential as a submachine gun cartridge. Which, to be fair, it wasn't terrible at. It wasn't as powerful as 9mm Parabellum, but it was smaller and lighter, so a decently-sized magazine could hold more and a soldier could carry more.

It meant, however, that if the pistol development continued as specified, the army would end up with a handgun and an SMG that used two different kinds of ammunition, creating just the sort of supply problem the pistol replacement project was intended to alleviate. With that in mind, the French Ministry of War declared in 1927 that the new SMG cartridge, which by that point had been redesignated 7.65×20mm (French) Long, should also be used in handguns.

This led to a new set of trials in 1930, this time with the specification that entrants should use the 7.65mm cartridge. No fewer than twenty-two entries were received for these trials. Typically, a few of them were chambered for cartridges that were not 7.65mm French Long, demonstrating that even 90 years ago, people were incapable of following simple instructions. Presumably with a resigned Gallic shrug, the trials board tested them anyway over the next three years...

... and adopted none of them. Instead, the outcome of the 1930-33 trials was a revised specification—in essence, it seems as if the trials board wrote a new spec which eliminated features of the 1930 candidates they found undesirable, in hopes of eliciting a new round of submissions that would be closer to what was wanted. In particular, the new specification reinforced the insistence on using 7.65mm Long, and required a magazine safety and a Browning-style tilting-barrel locking system based on that found in the Colt Model 1911 (the patents on which had expired by then). It also called for the fire control system (trigger mechanism, hammer, sear, and the spring to operate them) to be unitized, removable as one piece. (Interestingly, at about the same time, Fedor Tokarev was doing the same thing in his eponymous pistol for the Soviet Army.)

In the next round of trials, which commenced in 1935 and ran into 1937, there were only four submissions, the rest of the field having been thinned out by the tightened requirements, loss of interest by some of the former contenders, or both. They were:

The SACM entry was designed by one Charles Petter (1880-1953), a Swiss-born engineer who served in the French Foreign Legion during the Great War (and became a French citizen thereby). Interestingly, before the war he had worked for Krupp, the German industrial giant that made much of the Kaiser's artillery for that war. Petter's entry into the 1935 French pistol trials was essentially an improved 1911; it used the same tilting barrel/overhead lugs locking system, but eliminated the barrel bushing and incorporated changes to the recoil spring to improve accuracy.

The trials found the FN/Browning design to be durable and strong but "somewhat irregular in function" (possibly because it was a design adapted from 9mm Parabellum to the somewhat weaker 7.65mm Long cartridge), the MAS candidate to be the most reliable, the SACM entry to require some mechanical improvements (specifically strenghtening of the hammer strut), and the Star model to be the least suitable of the group, with numerous breakages in testing. Also, it was made by foreigners. (There is some contention that the Browning was ultimately rejected because it was Belgian, as well. Chauvinism is, after all, a French loan word. But I digress.)

With the requested changes made to its design, SACM's pistol was adopted as pistolet automatique, Modèle 1935A (the "A" standing for Alsacienne, not because it was meant to be the first in a series).

You may note that this is not the pistol we're actually looking at today. More on this in a moment. In the meantime, this is a Wikimedia photo of a Model 1935A.

That may look familiar to you. If it does, it's because the Swiss industrial company SIG (a German acronym literally standing for "Swiss Industrial Company"), which had apparently been watching the French pistol trials with interest, was so impressed by the Model 1935A that they licensed Petter's patent, spent 10 years tinkering with the design, and eventually put it into production as the SP47/8, which was adopted by the Swiss Army as the Pistole 49. Here is a photo from Wikimedia of one of the army ones:

Here in the United States, this very expensive handgun is better known as the SIG P210, which it was renamed in 1957. Gunsmith Cats fans in the audience may remember it as the only pistol protagonist and noted gun snob Rally Vincent will deign to use, if she simply must, when a grey-market first-generation Czechoslovakian CZ 75 is not readily to hand.

Anyway, to get back to how it is we're looking at a different Model 1935 here today: Despite the name, the Model 1935A was adopted in 1937 (it seems to be dated to the beginning of the trials that produced it rather than the end), and production took time to ramp up, so deliveries did not begin until 1939. Looking at European history, what else began in 1939?

Ah, yes. World War II.

SACM's rate of production might have done for rearming the French Army, in a fairly leisurely fashion, in peacetime. After all, the French had been in no particular hurry to develop their new pistol; it took them twenty years from the signing of the Treaty of Versailles to the first Model 1935As reaching units. Consider, however, the backdrop against which the actual adoption and start of production took place. In 1936, German armed forces reoccupied the demilitarized Rhineland, tearing up the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Agreement in the process. Early in 1938, the Nazis annexed Austria; later that same year Germany seized the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, and in the spring of 1939 they dismembered the country altogether. Meanwhile, on the other side of France, Spain spent the same period of time wracked by a brutal civil war that would end with a small-f fascist dictatorship in charge of the country, and in the southeast, the big-F Fascists had been in charge of Italy since 1922.

None of Germany's various acts of territorial aggression met with any response from the former Entente powers, including the French government, other than ineffectual throat-clearing, but to the people running the French Army, it was obvious that between Germany's rapid remarmament and obvious aggression, and similar governments in power in Spain and Italy, France was probably going to need all the guns before too much longer. By early 1938, it was clear that SACM's capacity to produce Model 1935A pistols was not going to cut it. Besides which, SACM was a civilian company, and its factory was in Alsace—uncomfortably close to the German border, in an area that had been disputed between the two powers repeatedly since 1871.

The French military authorities turned to one of their own arsenals, MAS, to make up the shortfall, and rather than task them with building more of SACM's design (as the United States armed forces would do with, for instance, the M1911A1), they retroactively adopted MAS's own entry in the 1935-37 trials as pistolet automatique, Modèle 1935S and ordered it into mass-production. Deliveries began in early 1939, actually slightly before SACM started coming across with Model 1935As.

And with all that taken care of, we can finally take a closer look at the one we have here.

Some accounts claim that the Model 1935S was merely the 1935A simplified for easier production, but this is not the case, as their profiles ought to make pretty clear. They have mechanical similarities, mostly due to the fact that they conform to the same trial spec, but they are entirely different in construction and share no parts.

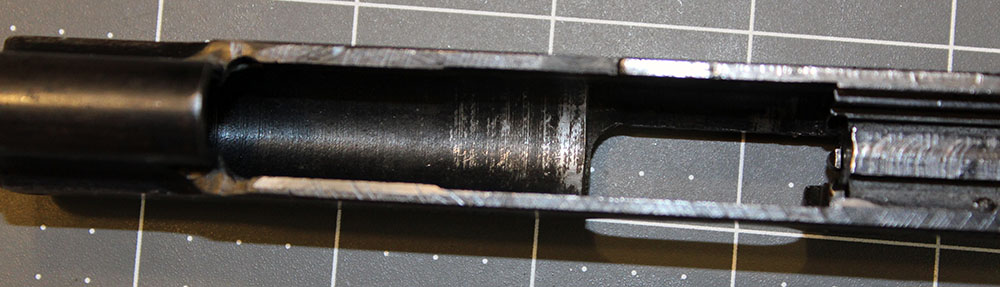

The Model 1935S is a pretty typical Browning-action locked-breech pistol design of the 1930s, mechanically quite like the 1911, but smaller and with some of the 1911's more annoying quirks addressed. This is fairly obvious once you take it apart.

There's nothing here that looks out of place for a 1911/Hi-Power-style pistol. Like the 1935A and the Hi-Power, Saint-Etienne's entry dispenses with the older design's barrel bushing, which addresses some of the inaccuracy inherent in the 1911's design, but it retain the earlier design's swinging barrel link. Once nice touch, which it shares with the 1935A, is the recoil spring being fully captive on its guide rod. It also has an unexciting single-stack box magazine holding, I believe, eight cartridges—not very many by modern standards, or even in comparison to the Browning candidate in the trials, but one more than the specification called for and, apparently, considered sufficient.

Disassembly is by opening the slide and pulling out the slide stop pin, then taking the slide and barrel assembly off the front, same as the Hi-Power (and many another pistol). As noted earlier, the trigger lockwork/hammer assembly can be removed as a single unit, but I haven't done that in this photo as it is kind of a pain in the butt (unlike in the Tokarev, where it's so trivially easy you can do it by accident).

The 1935S does have one mechanical feature that set it apart from the Browning designs it's based on, the 1935A, and, as far as I've been able to find so far, any other pistol then being made. Looking up inside the dismounted slide:

There are no cuts for the usual Browning-style locking lugs. Instead, the 1935S barrel has a ridge at the front of the chamber:

which locks against the top of the slide at the front of the ejection port. This is a locking method that went on to great prominence in some of the ubiquitous auto pistols of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, most notably the Glock 17 and its myriad descendents, but as far as I can tell, it debuted on the French Model 1935S, making it another of the Glock's "innovative" features (like the semi-DA striker mechanism it borrowed from the Roth-Krnka M.7) that were not so revolutionary after all.

Up toward the front of the slide's right side are most of this Model 1935's markings:

Being a military pistol, it has pretty straightforward markings. MODELE (oddly, not MODÈLE) 1935 S, CAL. 7,65 L, and the serial number. The "MAC" prefix on this gun's serial number means that it was built at Saint-Etienne's sister arsenal, Manufacture d'Armes de Châtellerault. MAC serial numbers for these guns ran in 10,000-gun blocks with a letter prefix, so the first 10,000 guns were serial numbers A1 through A10000, then the 10,001st one was B1, and so on. According to the table in Medlin and Doane's The French 1935 Pistols: A Concise History, which has been my main reference for this article, the serial number on this specimen indicates that it was made in 1952. The "M1" stamp indicates a modification to the design which was made by MAC when they started producing these pistols just after World War II, which we'll get into in a moment. First, let's have a look at the other side of the gun.

The only marking on this side is the M.A.C stamp that further indicates this gun was made by Châtellerault. Over here we also have the usual later-Browning-style controls, with a pushbutton magazine release just behind the trigger and the slide stop lever/disassembly pin above. One thing that's worth noting about the 1935S trigger is that it can be a little bitey. It looks like a pull-straight-back trigger, such as on the 1911, but it isn't—it pivots at the top—so in practice, if you don't have your grip just right, it can pinch your trigger finger in that gap at the bottom.

Up at the top rear of the slide is the safety lever, which is broken off in this example. It's in the FIRE position, and if the lever itself were still there, it would fit within that milled recess, flush with the back of the slide. On the original MAS 1935S design, that lever swung up and forward to the SAFE position, so that it lay parallel to the top of the slide. When they started production of the type in 1946, MAC changed that to match the way the safety works on the 1935A, which pivots the other way. In this design, the lever (if it were there on this one) swings up and back to go to SAFE, which means that when it's in that position it sticks out from the back of the slide, the idea being that it provides an instant visual and tactile cue to the operator that the safety is on.

(It's interesting to me that in one of his match videos, Ian McCollum of Forgotten Weapons discovered that this safety design has an operational drawback. Namely, if you're not careful about your grip when you rack the slide, you unwittingly switch the safety on in the process—if you don't let go fully and just let the recoil spring pull the slide out of your hand, as it slides past, your fingers effectively "wipe" the lever into the SAFE position. Since this is much more likely if the hand operating the slide is the right one, which implies a left-handed shooter, this was presumably either not noticed or not considered worth correcting in the original 1930s trials.)

At any rate, that's what the "M1" stamp over on the right side indicates, that this is a 1935S that's equipped with the 1935A-style safety lever. Since all the MAC-production guns were so equipped, it's a little redundant on this one, but I guess the French armorers of the time figured it was better to be explicit about these things.

The initial production run of the Model 1935S at Saint-Etienne began in early 1939, but was suspended in mid-1940 when the Germans rather inconveniently overran the plant. The same thing happened to the Model 1935A, of course, but there's an interesting difference between the two pistols' fates. SACM's plant in Alsace was occupied intact and operational, and the Germans, never ones to waste an opportunity to get free stuff, kept the Model 1935A in production for their own use, as they also did with, for instance, Hi-Powers at the FN factory in Belgium, the Polish wz. 35 Vis (a very similar handgun, and highly regarded in its time), and pretty much everything out of Czechoslovakia. In German service, it received the designation Pistole 625 (f), the "f" standing for "French".

In Saint-Etienne, on the other hand, although the arsenal fell first under German occupation, then the administration of the Nazi-aligned puppet government in Vichy, and then direct German occupation again after 1942, the Model 1935S was never made for German use. Whether that's because the Germans felt the plant's capacity would be better used producing other things for them (such as the MAS-38 submachine gun, which entered German service as the MP722 (f)), or exactly what, is unknown, but the Model 1935S never received a German designation, and there is no indication that the Germans ever used them, apart from possibly individual examples captured from the few French officers who had them when the war began.

(One story, which is repeated on Wikipedia but not present in Medlin and Doane's book, is that Saint-Etienne's engineers were able to hide the plans and tooling for the M1935S before the Germans arrived, so that the occupiers never knew about it. That seems romantic but less than entirely likely. Medlin and Doane only state that "no official explanation has been discovered," speculating that the Germans simply didn't want to adopt another weapon that used non-standard ammunition—although, since they had already taken on both the Model 1935A and the MAS-38, both of which also used 7.65mm Long, that explanation feels a bit weak to me.)

At any rate, production resumed after the war, and by the end of 1945 MAS had contracted out additional production to MAC (which, as noted above, got their line going in 1946), MAT (Manufacture d'Arms de Tulle, another government arsenal, which made parts for the MAC guns), and the private firms of Manufacture d'Armes et Cycles de Saint-Etienne (commonly known as Manu-France, presumably in part to avoid confusion with Manufacture d'Armes de Saint-Etienne, the government arsenal) and the Société d'Applications Générales de l'Électricité et de la Mécanique (SAGEM). The Model 1935S continued to be produced into the mid-1950s; the last MAC specimens were made in 1956.

By then, the Models 1935A and 1935S had already been replaced in French service by a new pistol, the MAS-designed Model 1950, which was adopted after a trials process that began almost as soon as World War II was over. The Model 1950 is a sort of hybrid of both 1935 models, in terms of its design, but chambered for 9×19mm Parabellum. Although the design came out of MAS and was largely based on the Model 1935S, they were initially produced by MAC and so are commonly called the "MAC 1950" by modern collectors. These were made into the 1970s, and ultimately superseded by the PAMAS, a variant of the Beretta 92F.

I'm not going to lie: I have one of these entirely because Ian did a video on them a couple of years ago and mentioned that, since ammunition for them was not in production at the time, they were pretty cheap on the collector market—and that he was trying to get someone to start making 7.65mm French Long cartridges again, hint hint. Since then, someone has started making 7.65mm French Long cartridges again, although I don't have any as yet.

In the ledger that all holders of an 03 (Curio & Relic) Federal Firearms License must keep of their collections, there is a note against the entry for my Model 1935S. There are notes against all the items on the list, usually indicating things like when they were made (if known), what accessories go with them (if any), that kind of thing. The one for the 1935S reads, "Châtellerault, 1952. Safety lever is broken in 'fire' position. Also, dang it, Ian."